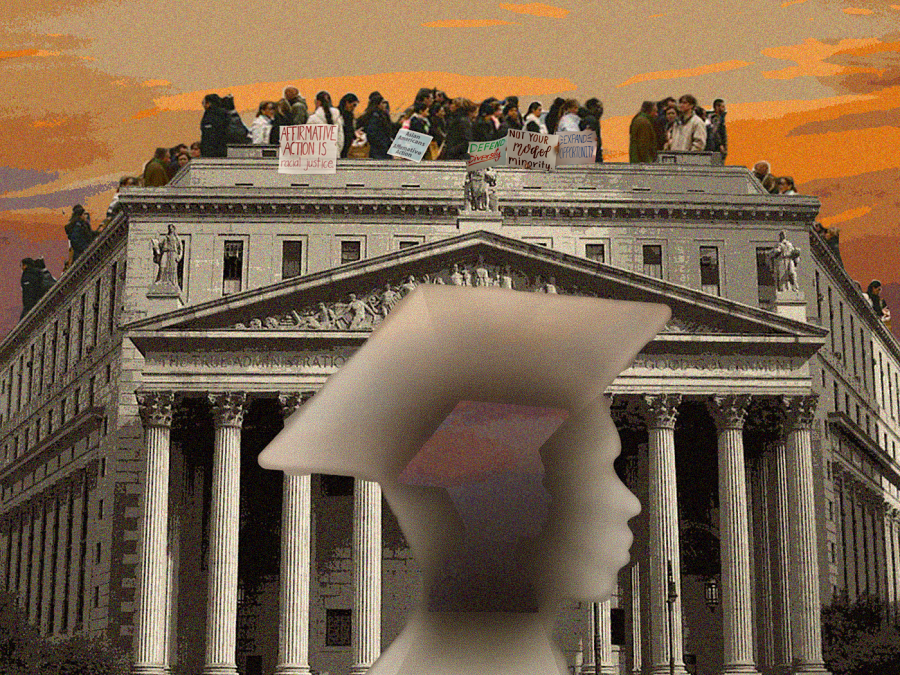

Affirmative action is on the line. UT must seek alternatives now.

November 11, 2022

A 2022 poll found that 64% of Americans support programs aimed at improving racial diversity of students on college campuses. However, this same poll discovered 63% would support the U.S. Supreme Court in banning universities from considering race and ethnicity when making admissions decisions. While support exists for the principle behind affirmative action, it’s clear many do not support the policy itself.

From its start, affirmative action has been contentious. Universities began implementing race conscious admissions policies in the 1960s and 70s to address structural barriers to higher education for underrepresented communities. Since then, the policy has been contested time and time again, debated both legally and in the court of public opinion.

On Oct. 31, the U.S. Supreme Court heard arguments for two cases that will determine the future of affirmative action in higher education. With a conservative supermajority and the doubts expressed by the six conservative justices, it seems likely that the Court will rule to ban race-conscious admissions policies nationwide. Not all universities incorporate affirmative action into their admissions process, but those that do — including UT — must prepare now for its potential overturn.

Following the ban of race-conscious admission policies in public Michigan universities, Black and Indigenous student enrollment at the University of Michigan has dropped by 44% and 90%, respectively. This ban passed 16 years ago, yet the university still struggles to improve enrollment rates for racial minority groups. Similarly, public California universities saw disproportionate declines in Black and Latine enrollment after the passage of a proposition that banned affirmative action statewide in 1996.

These universities elucidate the likely consequences of overturning affirmative action: enrollment rates of racially underrepresented student groups suffer. What, then, can UT do to help maintain a racially diverse student body?

If universities cannot factor race into admissions policies, they will have to rely on “race-neutral” alternatives, such as placing greater emphasis on socioeconomic status. While such policies are historically less effective than affirmative action in preserving racial diversity, universities will have no choice but to implement them if race-conscious admissions policies are outlawed.

Sanford Levinson, a UT professor of government and law, explained how a ban on affirmative action would impact minority communities.

“The honest answer is, nobody really knows, because as I’ve been saying, part of the answer depends on how clever universities or businesses or others will be in coming up with workarounds so we will no longer look at your overt ethnicity,” Levinson said. “My hunch is that the overall admission rate (of minority students) will go down.”

Levinson suggested other factors that universities could consider, such as whether applicants speak different languages or are the children of immigrants.

One “race-neutral” alternative is already implemented at UT: the “Top 10 Percent Law,” which currently guarantees the top 6% of high school graduates admission to public Texas universities. While this should help preserve racial diversity, we must also consider applicants who are not automatically admitted. These students are admitted through a holistic review process that factors in an applicant’s race and ethnicity. This process will have to change if race-conscious admissions policies are banned.

“We’re not going to speculate on future court rulings or their impact (on UT),” University spokesman Brian Davis said in an emailed statement.

UT administration may not want to speculate on the future of affirmative action, but it’s unrealistic to wait until the Supreme Court comes to an official verdict. As Levinson noted, the effectiveness of universities in preserving diverse student bodies will partly depend on the creativity of “race-neutral” alternatives. Developing these alternatives will be difficult and time consuming — requiring thorough planning, research and critical feedback.

Even if the Supreme Court preserves affirmative action, the issue will surely be contested again. When the Court voted to uphold affirmative action in 2003, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor expressed in the majority opinion that race-conscious admissions policies were not intended to be a long-term way to address a lack of on-campus diversity.

If UT waits to act until affirmative action is gone, it will be too late to preserve our diverse student body. We cannot continue relying on a highly contested policy that is likely to soon be overturned. There’s no clear or simple solution, but with a Court decision likely due in summer 2023, we must start looking now.

The editorial board is composed of associate editors Mia Abbe, Lucero Ponce, Alyssa Ramos, Michael Zhang and editor-in-chief Megan Tran.