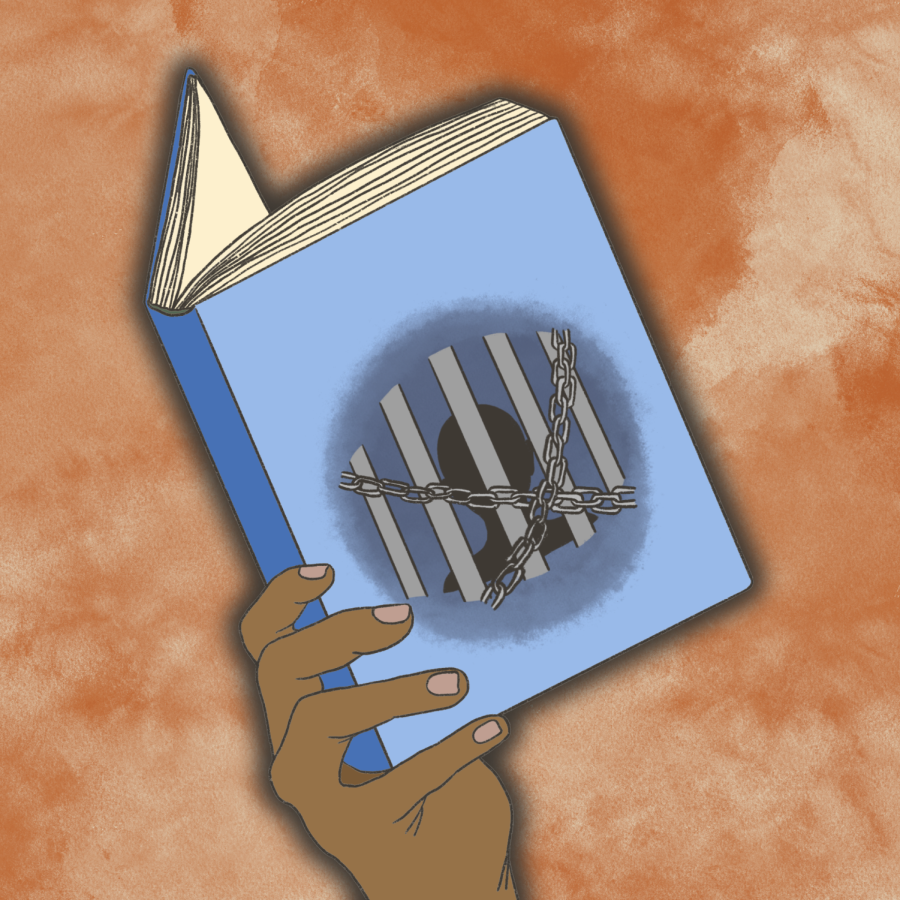

Discuss the connection between slavery and the American Prison system

February 19, 2023

In the past few years, Republican politicians have focused on limiting the discussion of race and racism in US history with the banning of critical race theory. In 2021, Governor Greg Abbott signed a bill effectively restricting the ways in which teachers can talk about America’s connection to racism.

While the connection between slavery and carceral institutions is undeniable, the US history public K-12 curriculum does not address the relationship at any stage of education. For many students, college may be their first introduction into learning about institutional racism. Therefore, core government classes at UT should detail how slavery originated American carceral institutions and systems because it still impacts us today.

During slavery, carceral institutions were less robust, but still present. Slave jails and Slave Patrols originated during Antebellum America as a way to trap and control slaves as they waited to be bought or if they ran away. This system also trapped free Black people.

The end of slavery created a large demand for the once free forced labor of Black folks. This demand grew through the domestic slave trade with the peonage system, which used forced labor as a way to repay debts, embodying slavery through a different name. At the same time, the southern convict leasing system also let the Southern states profit off of convicts, letting slavery continue through the penal system.

These systems evolved into modern day mass incarceration, a system that predominantly affects African American and Latine people, but also created Southern economic growth.

The roots of our modern day prison and justice system are intrinsically tied to slavery. It is important that we know this context in connection to our governmental institutions because otherwise we cannot solve the problems that face our country today.

“If we only consider institutions and the political process, the way they work now, we are not really considering the whole picture,” said Klara Fredriksson, a PhD candidate and assistant instructor at UT who taught GOV312L last semester. “You do need to understand the way that the institutions were structured from the beginning, so I think it contextualizes a lot of current issues that we see.”

Not teaching students about these connections is doing them a disservice as governmental institutions affect every lay person. We all have civic duties, like voting, and in order to fulfill them we must be knowledgeable of how our past factors into our present. This is especially important for UT STEM students who don’t have as much of an opportunity to explore this connection in their upper division courses.

Thomas Tran, a computer science freshman, explained that the only classes that would cover this vital connection are his core classes. In the history classes he’s been in, Tran felt that structural racism was brushed over.

“I think it’s really unfortunate as a STEM major, there’s very few things that are making me learn about anything regarding (the connection between slavery and government institutions) especially if you’re coming in with a lot of AP credits,” Tran said. “(Learning about the connection between slavery and government institutions) gives you more context for the sorts of policies that you want to support and the people you want to elect.”

STEM students need to be knowledgeable about government institutions and their history because they will inevitably interact with them in the real world.

“I think that by learning about these issues, students will be more knowledgeable about the pressing issues in our society,” said Talitha LeFlouria, Associate Professor of History and Fellow of the Mastin Gentry White Professorship in Southern History.

Core government classes at UT should aim to bridge this gap in knowledge to create more politically knowledgeable and independent individuals.

To bridge this gap, LeFlouria suggests “focusing on the Constitution and on the ways in which the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, but also allow for slavery to continue as a punishment for crime by examining the ways in which the 14th Amendment led to felon disenfranchisement for Black people who lost their right to vote if they were convicted of a crime.”

Educating UT students on the history of the US will create more empathetic professionals that further understand systemic racism and mass incarceration, allowing them to address these issues if they choose to.

“Oftentimes, we make assumptions about incarcerated persons based on what we believe and not what we know,” said LeFlouria. “And I think that understanding how structural racism works in this country, and how it is literally part of the nomenclature of our constitution will be an imperative for students as they move forward in their, in their careers and in their professions.”

Muthukrishnan is a government and race, indigeneity and migration freshman from Los Gatos, California.