Exams should have more oversight

March 8, 2023

As a pre-med student, I find myself on a path of high expectations – but with good reason. The stress of achieving perfection comes with the desire to help people, a responsibility no one takes lightly when charged with someone else’s well-being. But before reaching medical school, undergraduates first must struggle for high GPAs.

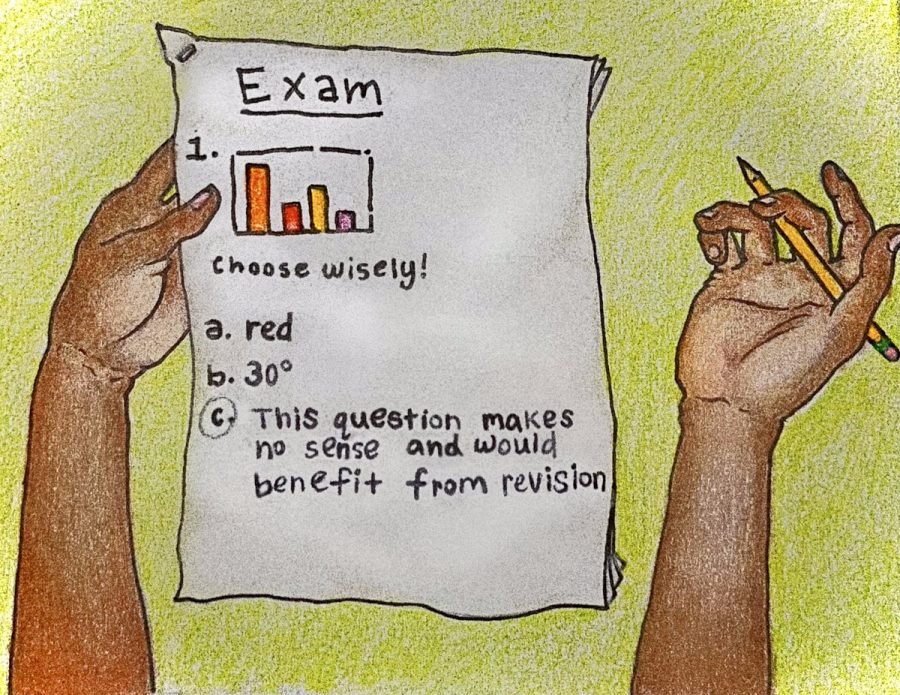

An emphasis on high grades can lead students to prioritize a perfect score over full comprehension of material. Consequently, students may shift their studying methods to cater to exam performance. While exams ideally serve as an accurate measure of knowledge, discrepancies between content and questions cause students to prioritize answering the “right questions.”

UT should implement a screening process for exam content to ensure clearer and fairer assessments in each course.

Although UT professors create and administer their own tests, the exam writing process varies by professor. The University provides faculty resources for “checks for learning” at the Center for Teaching and Learning, but does not standardize oversight of each exam’s creation.

According to their 2020-2021 Impact Report, the Faculty Innovation Center consulted with less than a third of UT faculty about teaching strategies. A lack of exam advising may contribute to a decline in course assessment quality, fueling an administrative culture of corrective action instead of preventive action.

While some professors develop exams with their teaching assistants, others may use their own discretion to create a test. But even though a professor may be an excellent academic, writing exams is an entirely different skill.

“I feel like (my professor) gave us so many materials, you can just memorize little steps and do well on that test. But I was not comprehending the chemistry,” said freshman biology major Yasmin Jenna Jackson.

Jackson ended the semester with an A in the class but still suffered from a lack of understanding. Many students fall into this cycle of memorize, test, repeat, which can lead to negative long-term consequences.

For pre-health students, sacrificing long-term comprehension for short-term benefits – such as pulling an all-nighter for an A – risks success in graduate school, where that foundational knowledge is needed. Even if a student does successfully complete medical school, there is no formula to succeed in real life that can be replicated via exam.

Exams should assess knowledge of course content both effectively and fairly. Ambiguous question wording can lead to inaccurate portrayals of students’ understanding.

To improve exam quality and overall education, a screening process could assess the content being evaluated and the way in which it is being tested, such as through comprehension and wording. This process could involve general oversight of an exam’s creation by a department advisor or even a TA, since TAs provide a medium of understanding between students and professors.

“I really like how we have undergraduate TAs who have taken the class because they can then relate it back,” Jackson said. “They know what to expect. Once you’re a professor and (a) graduate TA, you’re so deep in the content (that) it’s hard to realize, ‘Oh, wait, what should a freshman in an introductory class know?’”

To have students’ best interests in mind, professors should more carefully consider the quality of their assessments. By standardizing a screening process for its exams, UT can help professors more effectively evaluate students’ knowledge and in turn better prepare undergraduates for post-graduate success.

Monday is a health and society and Plan II freshman from Houston, TX.