Study finds East Austin neighborhoods impacted unequally by COVID-19 pandemic

June 22, 2023

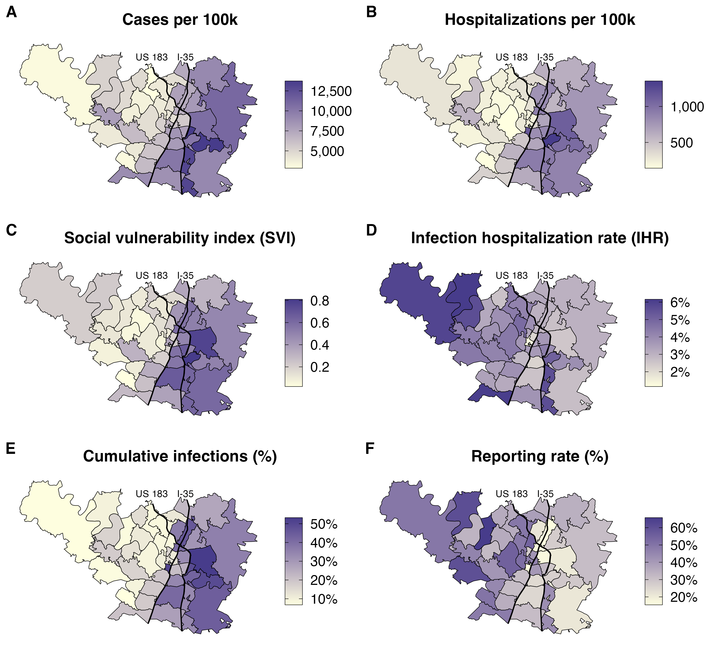

A UT study published on June 1 found that vulnerable East Austin neighborhoods were more likely to be at risk for COVID-19 hospitalizations despite recording fewer officially reported cases.

“Really early on with COVID, it was apparent that the public health interventions we were actually putting in place weren’t doing enough to prevent the inequality in infections and hospitalizations and mortality that we saw,” lead researcher Spencer Fox said.

Examining case and hospitalization numbers over the pandemic’s first 15 months, researchers referred to the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index to classify neighborhoods as “vulnerable.” The index considers factors like median income, community members’ age and neighborhood housing types. It then weighs these factors equally to determine how equipped a neighborhood is to handle a pandemic, researcher Emily Javan said.

“It’s a ranking of which community is the most and least likely to be able to deal with a catastrophe and rebound,” Ph.D. candidate Javan said. “In Texas, and in Austin specifically in this study, our higher social vulnerability zip codes had higher infections, and it wasn’t just due to being more likely to get hospitalized, it’s actually that more people were infected, we estimate.”

Although no one factor caused the disparities, factors such as “mobility” — having to leave home to work in-person — and a lack of public health knowledge contributed more than others, researcher José Herrera said.

“One important issue that we need to address is the communication of how important it is to know about the science of what’s happening in the population,” said Herrera, research associate at the Meyers Lab. “That unawareness that the general population had about how science works and how the disease is spread in the population was actually one main reason we had a huge impact of COVID.”

Javan said a historic lack of investment from the city also negatively impacted East Austin neighborhoods.

“Many places, like close to Del Valle, have food deserts … there’s a myriad of factors that could have led to this, and it does align with our pre-existing knowledge of Austin’s Eastern Crescent,” Javan said.

Fox, assistant professor in the Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the University of Georgia, said some measures the city took helped curb the spread of COVID-19 across vulnerable neighborhoods.

“The things that the city of Austin did well was trying to get testing resources into regions that they thought were most likely to have trouble accessing testing resources … then ultimately, trying to place vaccines where they’re needed most,” Fox said. “These communities have the highest infectious burden, highest rates of mortality and trying to vaccinate those communities to protect them really was a priority.”

Still, Herrera said the researchers continue to analyze how these neighborhoods could be better protected from future pandemics.

“This is not the first time that we have had a pandemic, and this is not going to be the last one,” Herrera said. “The most important part that we have to work on right now is to use the data that we have available to recognize where the most vulnerable populations are and how we can actually reach them through communications and through many ways that they could actually trust.”