UT professor and author Elizabeth McCracken recently won the Wingate Prize, a literary award given to the best book exploring Jewish identity, for her novel, “The Hero of This Book.” The novel follows the relationship between a writer and her mother while discussing the complexities of memory and the ethics of storytelling. The Daily Texan sat down with Professor McCracken to speak about her writing process and personal tie to the novel.

DT: What inspired you to explore this narrative arc?

EM: It’s a novel about a writer in London who’s walking around thinking about her mother who has recently died, and I was a writer in London who was walking around thinking about my mother who had recently died. … It is sort of talking about the difference between a novel and a memoir, and it plays with that notion that books can look like different kinds of books.

DT: How do you approach character development during the writing process?

EM: I try to think a lot about who my characters are physically first. I have to be able to see them. … The first thing that I know for sure is how tall all my characters are in (relation) to each other. This may be because I’m a very short person, and my mother was a very short person. My father was a very tall person. Knowing who my characters are physically helps me a great deal. But other than that, I try to listen to them talk. I try to figure out how they think. I try to be sympathetic towards any character I write, even the terrible ones.

DT: Your protagonist grapples with whether chronicling her mother’s life is an act of love or betrayal. Do you believe your novel contributes to the conversation surrounding the ethics of memoir?

EM: As I wrote (the book), I was thinking of my mother, and I was really worried that she would hate the book if she would have known about it. But when I finished it, my conclusion was that she actually would have loved it. She loved being the center of attention and so — being the subject of a book — she would say that I got things wrong. But I also think that she would see it for what it is — which is that when somebody dies, I think writers want to immediately write about them as a way to keep them closer, which is why I really wrote this book — because I was missing my mother, and I think she would appreciate that.

DT: Would you mind telling me about your mother?

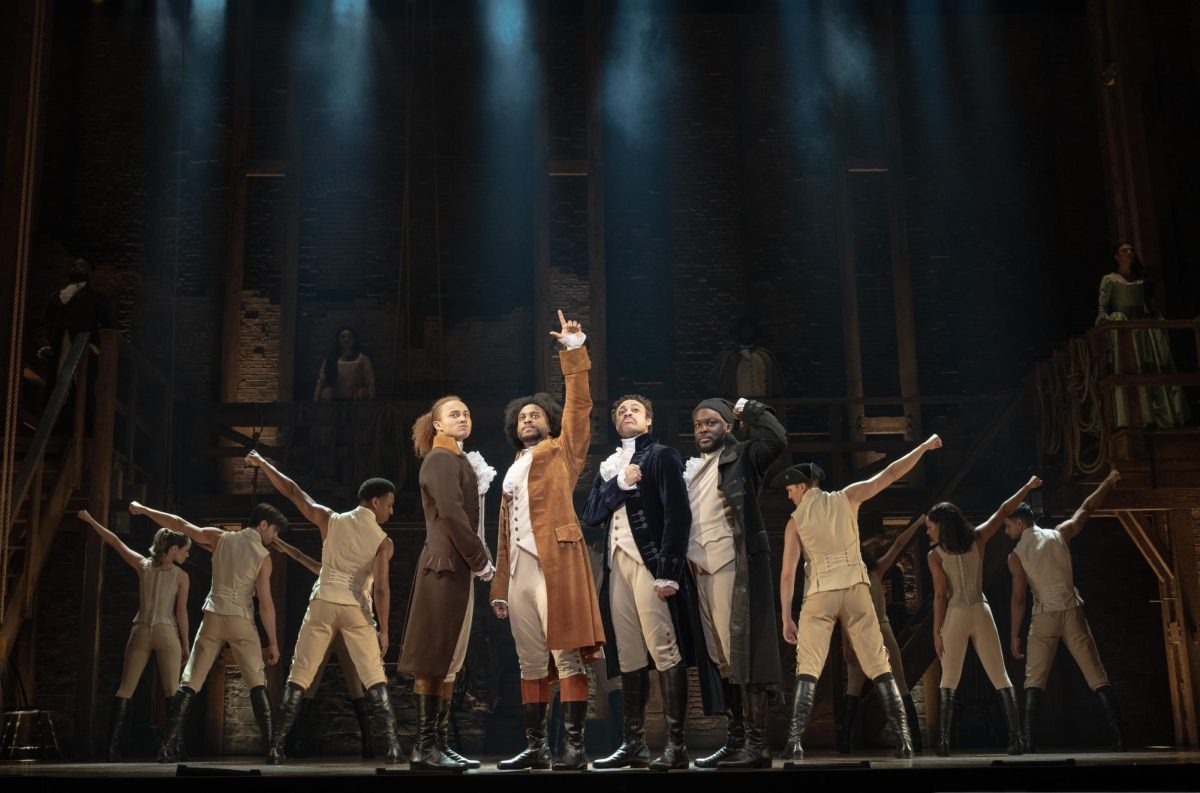

EM: There’s a lot more to her than is in the book, but she was a 4-foot-11, theater-obsessed, book-obsessed, editor and a writer. (She was) an extremely opinionated, extremely stubborn Jewish woman from West Des Moines, Iowa who had cerebral palsy. And a lot of the book is about how statistically unusual she was and how she loved being statistically unusual. She was also a twin, which she loved.

DT: How would you say the mother in the novel is different from her?

EM: I don’t think you can get a whole person in a book. When you write about your personal experience, with every passing year, the book you would write (will) be completely different. This is very much a portrait of my mother I wrote a year after her death.

DT: What do you hope readers take away from the novel?

EM: That’s definitely something for the readers to decide. I feel strongly that every book exists as a collaboration between the writer and the reader, so hopefully they will take something away, but I didn’t want to tell them what it should be.