“What starts here changes the world” — the University’s motto brands all promotional materials and is a hallmark of the school itself.

What starts here does change the world, but not in the way many think. It starts with academic and research resources, scholarships and campus operating expenses, which are partially funded by the 2.1 million acres of oil and gas fields located hundreds of miles away in West Texas.

These lands comprise the Permanent University Fund, a revenue source given to the University of Texas and Texas A&M Systems by the state Constitution in 1876. Almost 150 years later, over 22,000 wells generate the equivalent of 65,000 barrels of oil daily, creating the second-largest endowment in the nation.

UT System institutions received only a small part of the fund for the 2022-23 year, $934.2 million out of $32.9 billion. The remaining almost $32 billion is invested in a variety of entities, including the fossil fuel industry.

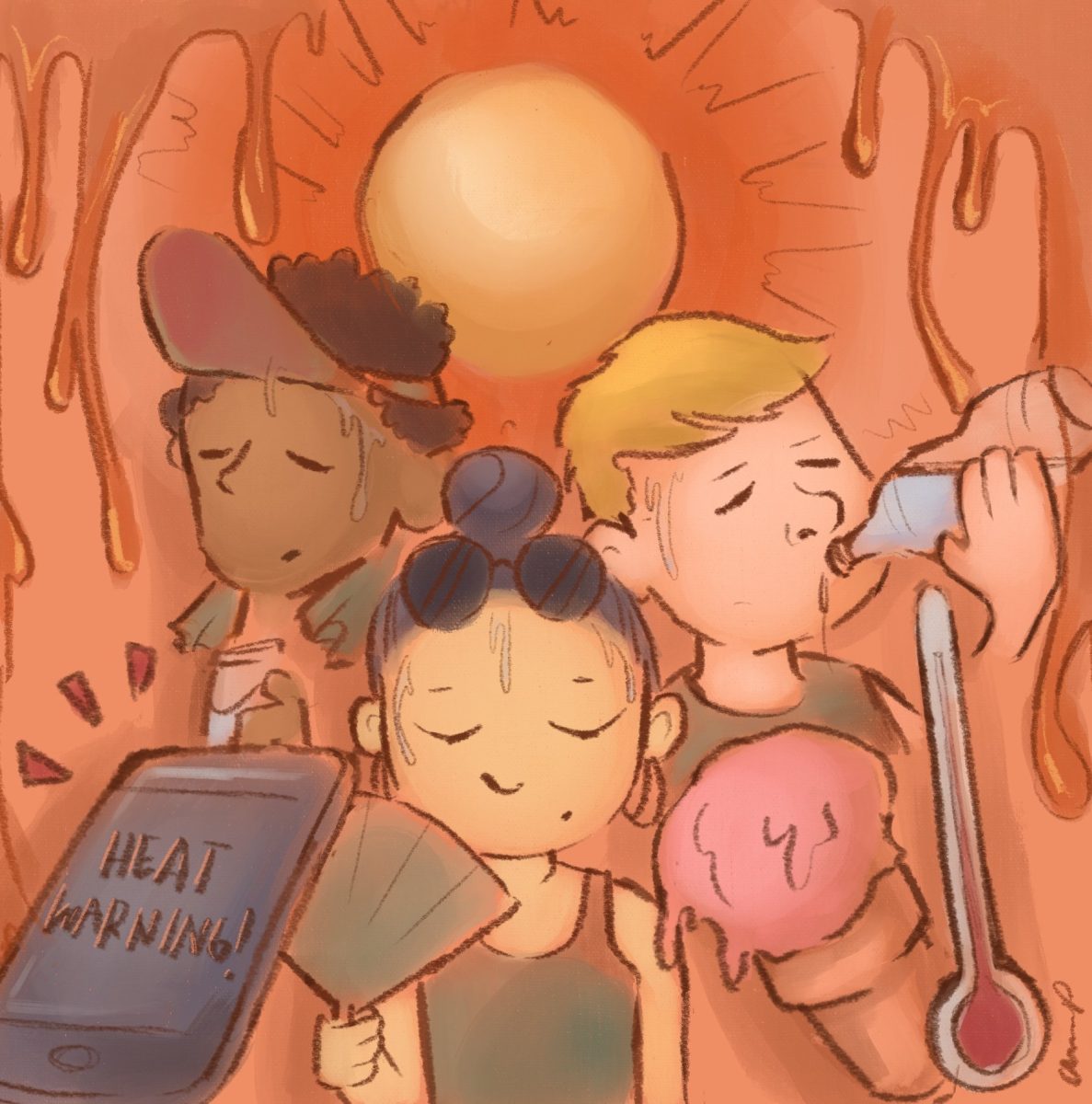

Environmental advocacy organizations have called for institutions, including the UT System, to divest from fossil fuels in the name of climate change. However, a fundamental issue lies not in where the money is coming from, but in where it’s going.

FLOWING LIKE OIL: WHERE DOES THE MONEY GO?

Income from the 2.1 million acres is gathered in two streams — mineral income via oil and gas, and surface income from land leases. Of the $32.9 billion within the Permanent University Fund, only surface income is supposed to be annually distributed via the Available University Fund because of mineral incomes’ nonrenewable nature.

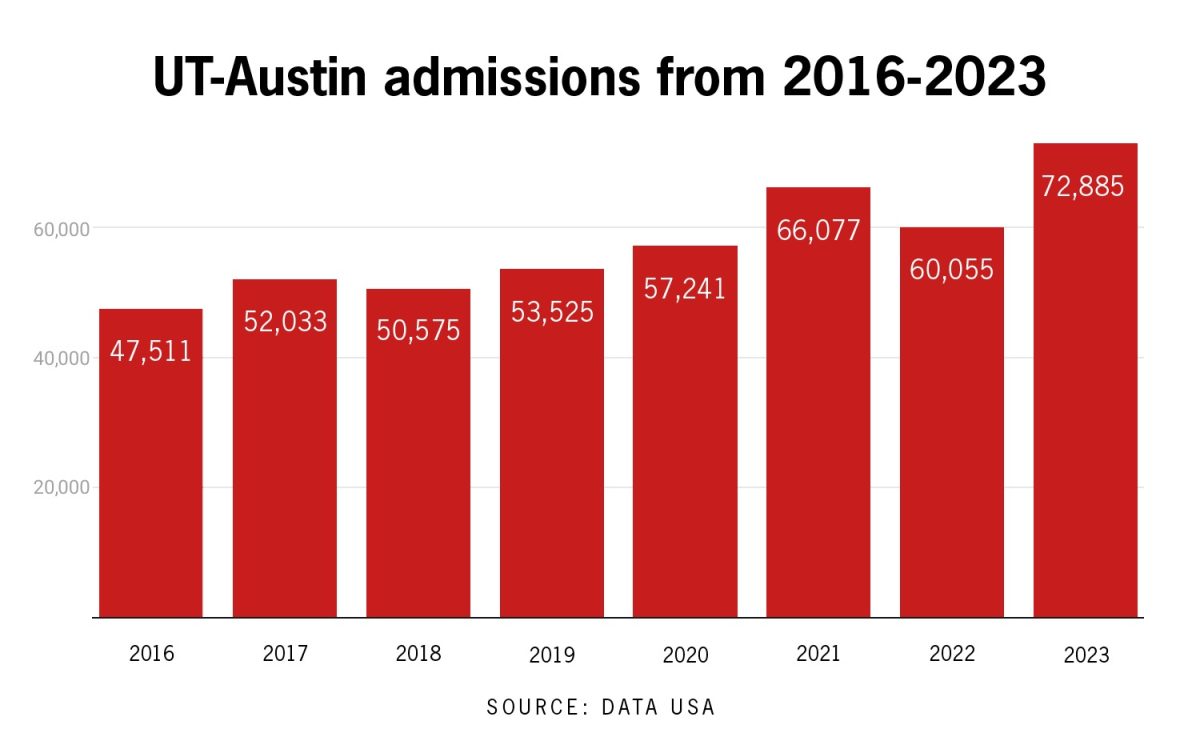

The State Constitution dictates that one-third of the Available University Fund be allocated to the Texas A&M System and the remaining two-thirds to the UT System. For the 2022-23 fiscal year, out of the UT System’s $934.2 million portion of the Available University Fund, $481.1 million of that is directly distributed to the flagship Austin location.

At UT-Austin, 13% of the school’s $3.97 billion annual budget comes from the Available University Fund, with over half of the total budget used for staff salaries and benefits. The remaining budget is spent on various areas, including 10% on scholarships and financial aid.

The remaining funds from the Permanent University Fund are invested in stocks, bonds and private equities under the direction of the University of Texas and Texas A&M Investment Management Company. This company endows the money in “any kind of investments” in amounts “consider(ed) appropriate,” according to the investment policy statement. They did not respond to requests for comment.

A specific set of criteria called environmental, social and governance investing was developed within the past few decades to ensure the use of moral and ethical standards in investing, said Derek Seidman, a contributing writer for corporate watchdog research group Little Sis, who focuses on the connection between fossil fuels and university endowments. He said in Texas’ politically adverse climate, these investments are a contentious point.

“There’s a critique coming from the right and a critique coming from the left,” Seidman said. “Being in Texas, there’s a big movement by right-wingers to now criticize ESG to try to divest or stop doing business with companies that use ESG as a standard.”

In 2023, the state proposed legislation banning the Permanent University Fund specifically from divesting from energy investments because of an increased use of ethical investing techniques, according to the bill. Examples of this include investigating prospective companies’ decarbonization goals and labor practices, according to Seidman.

FOLLOWING THE FUNDS, WHAT THE DOCUMENTS HIDE

The almost $32 billion of the Permanent University Fund not distributed to the Systems through the Available University Fund is invested in a series of companies and entities through stocks and bonds, some of which represent company ownership or simple financial assets. These companies, along with the amount invested, change on a yearly basis.

In the 2023 investment schedule for the Permanent University Fund, money is invested in thousands of companies. Research into the energy and materials sectors reveals finances in fossil fuel giants like the ChevronTexaco Corporation, Exxon Mobil Corporation and ConocoPhillips Company, which funded the controversial Willow Project. Seidman said there are also companies invested in that, while not directly funding fossil fuels, still support the industry.

“There is a movement towards divestment from fossil fuels. … That’s not the case in Texas,” Seidman said. “There’s other ways that universities also invest in fossil fuels. For example, you’ll often see in the portfolios that universities are invested in different financial funds and the funds will have different names.”

Investment in these companies, Seidman said, is partially influenced by the Board of Regents, the governing office for the UT System composed of nine members appointed by the governor. Out of these nine, almost half are in some way connected to the fossil fuel industry. The System did not reply with a comment in time for publication.

These regents, while not directly managing the investments themselves, oversee the lands and ensure the maximization of potential revenue through “intensive management, accounting, conservation and environmental programs” to “protect their interests” and promote environmental awareness, according to the System. Of the $934.2 million sent to the UT System, roughly $56.1 million is sent to System administration, including the regents, which Seidman said influences their desire to prove the investments’ financial success.

THE MORAL AND ETHICAL DILEMMA

In 2021, Harvard announced its plan to divest its endowment from fossil fuels after a nearly decade-long fight from student organization Fossil Fuel Divest Harvard, and two years later, it remained the nation’s largest-endowed university. At UT, Students Fighting Climate Change are engaging in the same fight, but on a different battleground.

Organization officer Madeleine Lee said because of the University’s location in the South, oil and gas is a deeply ingrained part of its history. While divestment is the ultimate goal, she said, the integration of moral and ethical investing techniques would be a positive progression.

“UT has more ties to fossil fuels than a lot of universities and groups — not just in investments but with the lands, with donors,” said Lee, an electrical computer engineering sophomore. “As an institution that’s trying to be a publicly beneficial institution that supposedly has knowledge and foresight, we should be taking these things into consideration.”

While the University only gains money from the Available University Fund, which excludes gas and oil income, Andrew Dessler, an atmospheric sciences professor at Texas A&M, said the decreased land value once oil eventually runs out — which is predicted to happen by 2052 — could potentially impact the income heading towards university-bound funds.

Past students have raised concerns about UT’s financial future after divestment as the Available University Fund provides 13% of the campus’ annual budget, including financial aid.

However, after Harvard’s divestment in 2021, tuition remained relatively stable and increased by less than 3% over the next two years, with no reported program cuts — a fact Lee partially attributed to an argument about Harvard’s responsibility to provide high-quality education and opportunities without investing in companies that potentially hurt students’ futures.

Dessler said the divestment decision requires both an understanding of its historical relevance and a willingness to work towards cleaner, alternative energy sources in the future.

“Fossil fuels have gotten us where we are today — we should tip our hat to them and say thank you for your service,” Dessler said. “The debate over climate (and) fossil fuels is really about what’s the energy of the future. If we continue burning fossil fuels, the planet and civilization (are) going to pay a very high price.