Editor’s note: Professors quoted in the article are speaking as individuals and not on behalf of the University.

UT medical researchers have found the future of their research uncertain after new guidance from the National Institutes of Health implemented under the Trump administration attempts to reduce funding for administrative costs associated with medical research on Feb. 7 and initiated hiring and travel freezes on Jan. 22.

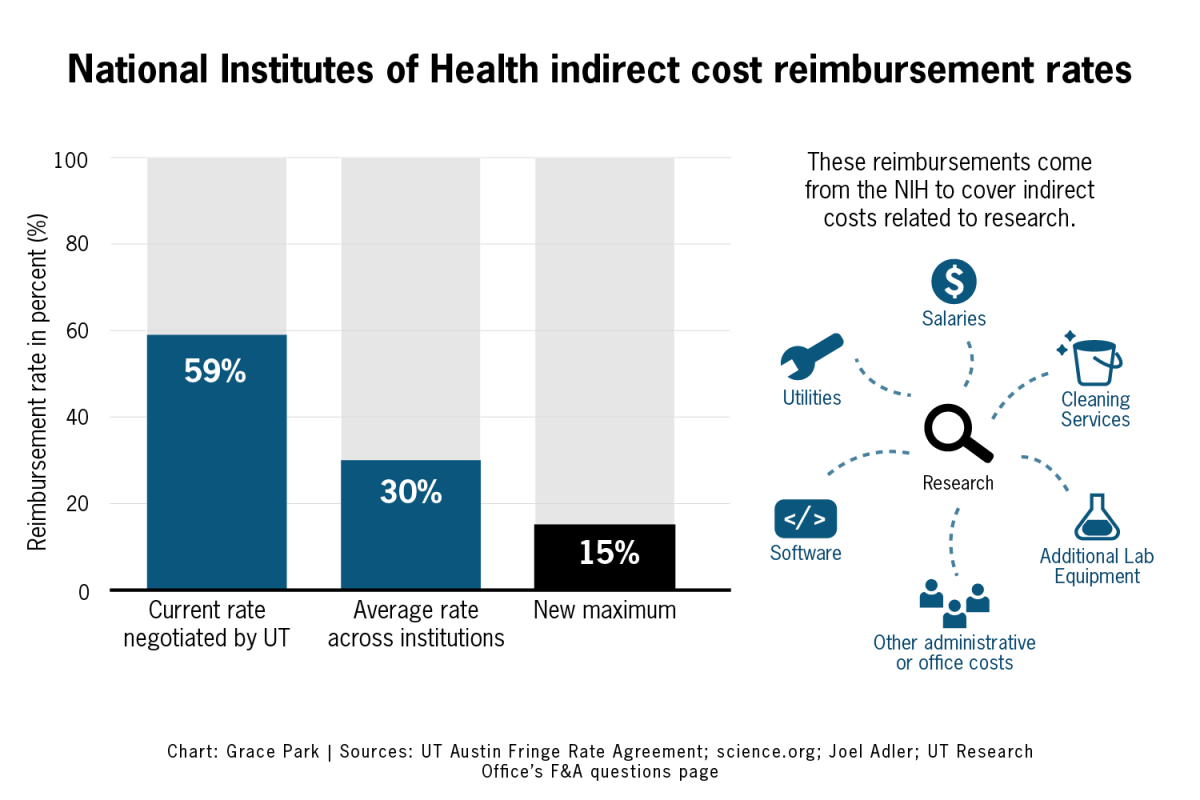

The NIH, the world’s largest medical research funder, announced multiple new restrictions, including standardizing and lowering the “indirect cost rate,” which the NIH said provides researchers additional money on top of direct grants to cover administrative office workers, building maintenance services and shared laboratory equipment. The Jan. 22 order also implemented a communications pause, preventing researchers from traveling and holding grant review panels.

“(The uncertainty) certainly raises some anxiety around for researchers who are trying to plan (a) long-term research project,” psychology professor Christopher Beevers said. “Not knowing what our research infrastructure may look like a year or two years from now is a little bit unsettling.”

According to a memo sent to faculty on Feb. 10 by Daniel Jaffe, the vice president for research, the University had previously negotiated for researchers to receive up to an additional 59% of their direct costs, or funds used directly for research, to be used on administrative and facility expenses. However, the new proposed rate would lower the indirect rate to 15% across all institutions, potentially causing the University to lose $16 million.

The Association of American Medical Colleges and 22 states filed a lawsuit against the order on Feb. 10, which has a hearing scheduled for Feb. 21. A Massachusetts judge temporarily blocked the order since the lawsuit’s filing.

“Effective immediately, the University will begin updating the (facilities and administrative) cost accrual for NIH-funded grant accounts accordingly,” Jaffe wrote in the memo. “However, the announced changes will not impact (researcher’s) direct cost budgets for ongoing projects. (Researchers) may continue to make expenditures on NIH grants as before.”

Joel Adler, a professor and researcher at Dell Medical School and a transplant surgeon, said while he has not heard any discussions of big layoffs, the cuts could manifest in other ways.

“Let’s say there (are) five financial coordinators, for instance, that serve the medical school,” Adler said. “Suddenly, when one of them leaves for whatever reason, (UT) won’t rehire (for the position).”

Beevers said he was uncertain how the cuts would affect his and his colleagues’ research, but he is concerned it would require significant changes to the funding process.

“It seems to me like it would be really difficult to predict and budget for those ongoing costs of maintaining facilities if you don’t know exactly which grants are going to get funded and how much revenue is going to come in for research that would support research infrastructure,” Beevers said. “Doing it the way it’s been done probably makes it a little bit more predictable in terms of what sort of budgets to expect than trying to bundle it into a bunch of individual grants.”

UT covers research costs upfront and awaits reimbursement from the NIH, Jaffe said. He said researchers should continue to process expenditures as normal, but the new restrictions would significantly reduce what the NIH will reimburse.

“The affirmation is just ‘Keep on going like nothing’s happened’ because you don’t know what to expect and when the next lawsuit is going to change it and everything else,” Adler said. “Everything’s so chaotic right now — this is just one small slice of chaos.”

The NIH also rescinded any offers for jobs set to begin after Feb. 8, according to an email obtained by Science, a peer-reviewed weekly journal. The Trump administration imposed recent restrictions on NIH’s parent agency, the Department of Health and Human Services, leading to canceled grant review panels and halted communications with researchers over the past two weeks.

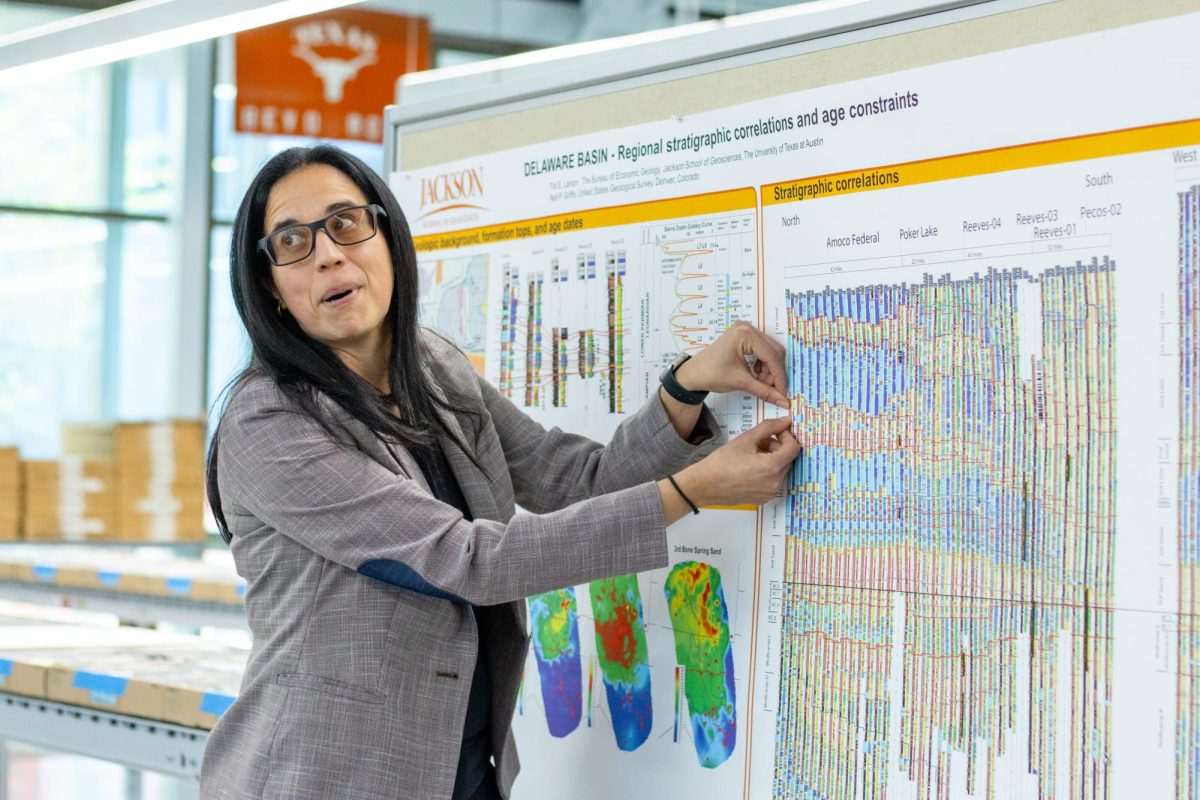

One of those researchers is Ann Majewicz Fey, an associate professor at the Cockrell School of Engineering with a courtesy appointment at Dell Medical School. While Majewicz Fey’s allocated funding has not expired, she said the communication gap between researchers and the NIH has led to uncertainty about projects, including her work on fetal surgery robotics.

“Really the biggest thing (is) that (the) communication channel is paused,” Majewicz Fey said. “I was supposed to be on a panel (to review other projects) this week, and that’s usually a two-day thing where I just go teach my class (and) review other people’s proposals, and that is a significant time effort. I know that those were canceled.”

Majewicz Fey said the grant system typically shields researchers from disruptions to their day-to-day work because they are not paid directly from the NIH until after they make purchases, so they are not directly losing access to funds. At this time, it is unclear whether the communication gaps will affect the reimbursement process, she said.

Adler said in an email that both his and his colleagues’ work had critical funding meetings postponed and altered in the past two weeks.

“I’m not sure what the status of their council meetings is,” Adler said in an email statement. “(On Feb. 5), I had a grant due to the NIH for a five-year project. The most significant change we made was to remove any mention of disparities and diversity from the public-facing documents that you could find on the internet.”

Adler also said this uncertainty could deter early-career researchers from pursuing medical research. Michael Kasman, a graduate student and research assistant who recently applied for an NIH fellowship to study robot-based fetal surgery, said he’s unsure how the funding uncertainty will impact his project.

“My advisor told me about the whole problem like the NIH froze or something, but I got an email, like the day before or something like that, about updating my application if I have any supplemental materials to put in,” Kasman said. “I’m not 100% sure if the freeze affects me.”

Majewicz Fey said funding slowdowns could harm less profitable medical research that receives less support from private companies.

“(Less profitable research is) underfunded in general for lots of reasons, especially for pediatrics and fetal because the commercial markets tend to be so small for (the) technology,” Majewicz Fey said. “There (are) not a lot of companies that support technology development for that population, and that’s often why the needs are so great because there are no companies that are building surgical technology.”

Adler said the overall funding uncertainty could slow future medical innovation and the situation could create setbacks in the future of medicine, including funding research on gender and ethnic differences in medicine.

“COVID-19’s most significant challenge was the pace of science just slowed considerably — trial enrollment was slower, reduced access to research facilities and overall shifts in priorities — caused by an appropriate shift toward COVID-19-related research,” Adler said in an email. “Any funding slowdowns or delays will have a similar effect. … With COVID-19, there was always a presumption that things would get better, but now, I’m not so sure anybody feels that way.”