Many people often find themselves scrolling through a war of outrage online. A politician’s remark starts an X feud, a false story creates a Facebook debate and a TikTok video turns into a conflict between opposing sides. If you ever feel as if social media apps are pushing enraging content to you, that’s because they are.

According to Science Direct, because of college students’ constant social media usage, they are widely exposed to misinformation online. Social media platforms are designed to maximize engagement, and studies show that outrage is one of the most efficient strategies for keeping users engaged. However, this causes false information to circulate faster than factual information online, giving people an inaccurate understanding of the truth.

“When (users) are frustrated, (they) are more inclined to comment on something or to respond to someone … so whether unintentionally or intentionally, this does get picked up by algorithms,” said Josephine Lukito, assistant professor in the School of Journalism and Media. “(Social media platforms) notice that more individuals are becoming engaged in either sensationalized content or content that makes people angry. And so they then amp up that content.”

Social media doesn’t just reflect societal divisions, it deepens them. As public trust in traditional media declines, people are turning to alternative sources of information, such as extreme partisan media and influencers who are not held to the fact-checking processes of traditional journalism.

Engagement is the vitality of social media, and online outrage isn’t just a byproduct — it’s an essential component of its business model. Advertising generates income for platforms. The longer consumers remain on a platform, the more advertisements they see. Companies favor content that appeals to emotions over reason, which keeps consumers engaged but results in the rapid spread of misinformation.

“The internet is a huge factor for why misinformation is spread more rapidly these days,” communication studies professor Nik Palomares said.

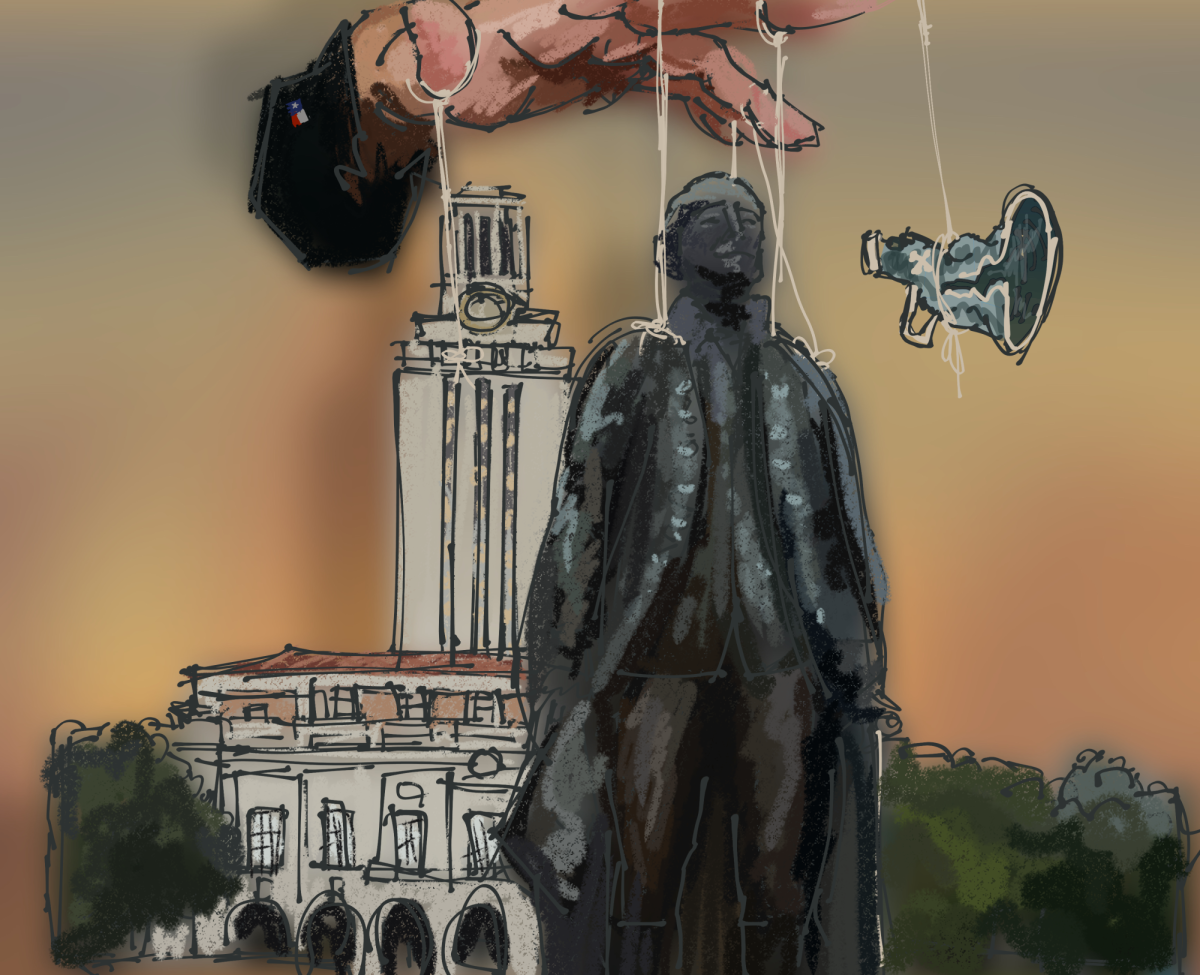

False information is widespread. From elections to public health, one of the main challenges in combatting misinformation is its protection by the First Amendment. The government’s limited ability to control information online without infringing on the Constitution makes it difficult to hold platforms liable. The case of NetChoice, LLC v. Paxton, where federal courts blocked laws restricting the moderation of online content, allowing social media companies to remain unregulated and free to profit from anger-inducing algorithms, exemplifies this issue.

Although social media increased the spread of false content, there has always been fake news. From the short era of yellow journalism in the late 19th century to propaganda in war politics, it’s not new for media companies to prioritize false and exaggerated news to spark reactions and boost engagement. However, today’s platforms spread outrage at greater speed than in the past, making the problem more difficult to control.

“Anyone can produce content online, and so it’s not just about journalists engaging in sensationalism,” Lukito said. “It’s about your influencer or an opinion leader or someone you trust, or a stranger on the internet that can make you as riled up as any journalist might have been able to in the past.”

The effects of misinformation have caused societal division, political polarization and public mistrust in the media.

While it’s hard to completely eliminate misinformation, platforms should prioritize accurate information over controversy. As users, we must recognize how algorithms manipulate emotions and be cautious when consuming content online. By verifying statements and obtaining information from trustworthy sources, users can take a role against false information.

Vazquez is a journalism freshman from Monterrey, Mexico.