JJ Hermes | Daily Texan Guest Columnist

The TAAS generation is a dying breed.

Consider this: Next year’s crop of freshmen never touched a TAAS test. They would have been third graders when the TAKS replaced the TAAS as the state’s answer to the question: Are our children learning? Now even the TAKS test is defunct, replaced and revamped by the so-called STAAR test.

We live in an education environment defined by standardized testing. It’s a terribly dull, uncreative and stunting way to quantify learning. But it’s the way we are teaching our children in America.

By the time I finished my SAT, having conquered the standardized test of all standardized tests, it struck a nerve that my first-year undergraduate classes were so packed that the evaluation of the stirring and poetic things I learned in lectures required a No. 2 pencil and eraser smudges. Only in smaller, upper-division courses could my exams be answered in ink.

Loath as I am to admit it, as a graduate student, I have turned into quite the Scantron machine myself, writing and rewriting some 200 multiple choice questions every semester. I am now but a cog in the standardized testing apparatus, a purveyor of right and wrong for the masses.

Sad to say, I’m resigned to think there’s no better way.

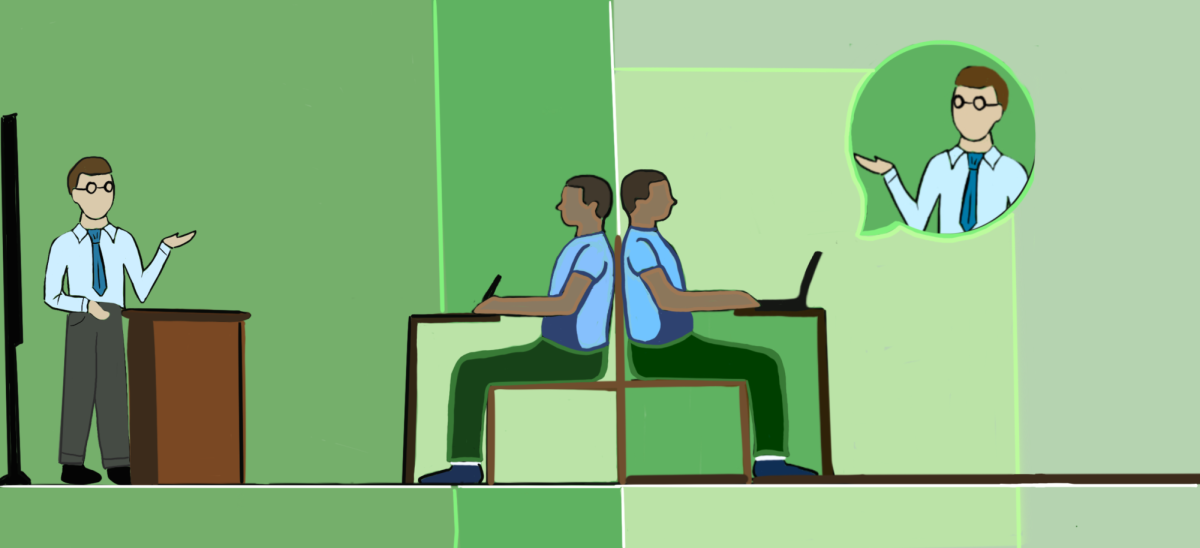

I serve as a teaching assistant for an introductory astronomy class that enrolls more than 200 students. This year we have two sections totaling more than 430 undergraduates. (Eat your heart out, Rick O’Donnell! That’s $400,000 in “faculty productivity!”)

One of my favorite parts of being a TA is giving an astronomy exam review. It’s an opportunity to cram six lectures which together constitute a tour of some of the most beautiful and curious things we humans know about our universe into one hour.

Inevitably, though, at the end of every review, a hand will slowly raise. “What will we need to know about Kepler’s laws?” “Is lunar libration going the be on the exam?”

It used to really irk me, the idea that my reviews weren’t a chance for me to blow these students’ minds but rather a venue for them to know exactly what to study. Until I realized there’s no metaphor about it: We are literally feeding their exam — which represents their knowledge about the universe — into a machine.

These students, some probably proud to see themselves as consumers in the classroom, have no reason to avoid seeing right through my idealism. Quite a few are not in college to explore the unknown and come away with a wider appreciation of the world and the universe. They have been trained on standardized tests. Many are taking a science elective because they have to, and the only way for them to pass is to fill in the pre-ordained number of correct bubbles.

This week, the charade continues as nearly five reams of paper will go through a photocopier in the form of our second exam. I am thus forced to be creative in the medium with which I’m presented.

And I have the opportunity to compose questions such as, “We orbit but one of the hundreds of billions of stars in the Milky Way, which is but one of hundreds of billions of galaxies in the universe. However, our best estimates indicate that all directly observable, normal matter (such as the stars, planets and people we see around us) comprise what percentage of the total mass and energy of the universe?”

It may only marginally assess your competence in astronomy. But it should blow your mind.

Hermes is an astronomy graduate student.