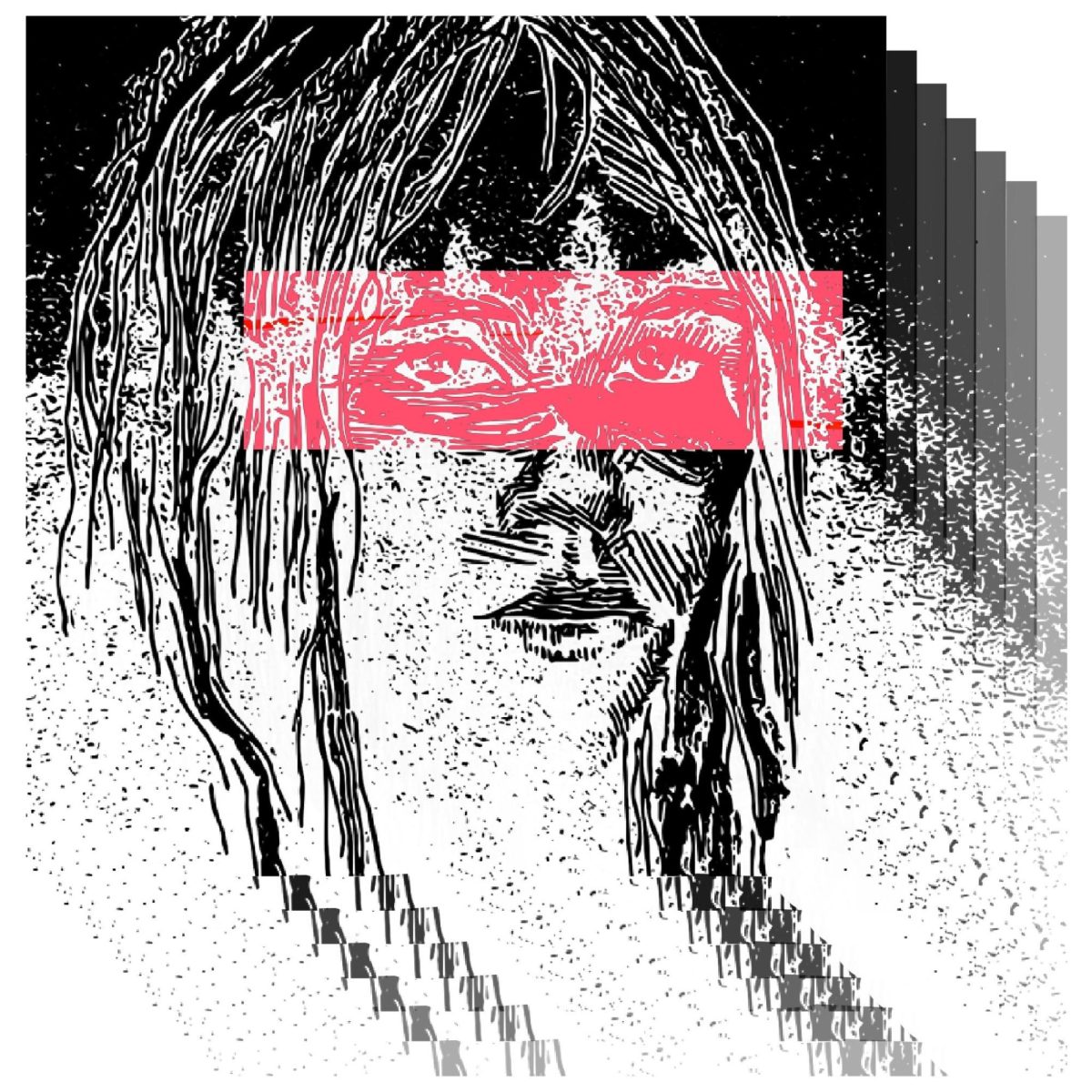

As quickly as she became Internet famous, Lana Del Rey has become a divisive songstress. Her “gangster Nancy Sinatra” (as her publicist would have it) eyebrows, music video vamping and droning, and sultry bellowing come across as either the top of the pops or unremarkable. When she croons, “It’s you, it’s you, it’s all for you … everything I do,” on her breakout single “Video Games,” you believe every word of it, but it remains elusive where those intentions lie on her album Born to Die.

Formerly as the singer of plaintive, Fiona Apple-like songs under her given name, Lizzy Grant, she released an album in 2010 that didn’t gain any traction, and she quickly performed an about-face. Lizzy Grant failed, and Lana Del Rey emerged a polarizing Internet-buzz artist.

It’s curious, her decision to scrap her career plans for a redesign: Has she shrewdly taken hold of the media-management behemoth necessary to become a successful singer these days? Or is she just its latest, most tragic victim?

Del Rey is no Lady Gaga. Gaga craftily pulled pop’s greatest bait and switch by first serving up middling dance music so she could turn around and do what she really loved: pure ’80s bombast. But she’s no Rebecca Black either: In a post-“Friday” world, where little production companies churn out slapdash music videos for young girls, we, Del Rey included, are all a little too smart to play the helpless victim.

Lana Del Rey (artist, image, person) and Born to Die are a completely disinterested Lizzy Grant playing along just enough to meet the minimum requirements of a pop star. She’s reached the third wave of self-awareness in the pop canon, where meta becomes self-loathing, where Lizzy Grant knows she has to be Lana Del Rey to be a star and hates every second of it.

Occasionally, she makes the best of it, including on “Video Games” and “National Anthem,” a campy, summery burst that includes the bizarre interpolation of rap verses, a la “Friday.” However, on most of Born to Die, she goes for artificial sweetness; those budget-spy-movie echoes and trills in “Blue Jeans” underline the album’s trifling, forgettable production effects. Not that it’s not a blithely enjoyable song — everything about the Del Rey personage and Born to Die seem engineered to be just the right amount of stirring for everyone to pay attention but not quite enough to be convinced of its greatness.

Those purely synthetic qualities make the album nearly impervious to curdling. On “Diet Mountain Dew,” it’s like Del Rey is taunting us: “Baby you’re no good for me, but baby I want you, I want you.” And “Off to the Races,” in which she embodies kitsch in the form of a “barrio” sex kitten, is a meandering, off-the-wall blitzkrieg. It’s her “Friday”: abhorrent but tuneful; a parasite awaiting your aural host.

It’s her voice, both vaguely operatic and restrained, that draws you into Born to Die’s diminutive sonic and narrative breadth. There’s only one score: moody chamber room strings. All the lyrics tell of her longing, pining, needling for the guy (or is it us?) to come back and love her and that she’s barely dressed and a little drunk. The production and hand wringing is exhaustive, but her voice deserves its own character study; it seems to exist and operate from a completely different place than the person it pours out of.

Born to Die is an album of probing fascination that’s hard to love. But when examined purely as an exercise in the production of a pop artist in 2012 — or what Lizzy Grant and her producers and agent think constitutes a modern pop act — it becomes an intriguing process album. The artist behind the music in this album, this experimentation, this construction, ultimately comes across as removed; but her voice comes through. Perhaps at some point, Lana Del Rey‘s levels of managerial- and self-negotiation will reach a mutual agreement.