Because of the Northwestern University football team’s recent vote on whether to unionize, momentum both for and against further financial compensation to college athletes has increased dramatically. Citing a need for broader health care as well as fully guaranteed scholarships, supporters of the at least partial unionization of college athletes argue that some college athletes deserve further compensation, “compensation” that extends farther than the reaches of a scholarship as presently constructed.

Detractors, on the other hand, find a number of reasons not to compensate. They argue that amateur status paired with sentiments of “love of the game” define our romantic notion of what a volunteer student-athlete ought to represent.

And yet both sides of the argument revolve around perceptions of fairness and whether or not we are treating equals equally.

The real answer should lie somewhere in the middle, however, where athletes first receive full scholarships before any further compensation is granted.

USA Today recently reported that University of Texas athletics amassed $165.7 million in operating revenue in the academic year 2012-2013, $109.4 million of which arrives directly as a result of the football program. This was the largest revenue-producing year in the history of UT athletics, and when we consider the increasingly profitable Longhorn Network, not to mention the excitement surrounding new head coach Charlie Strong, we can reasonably conclude that that $165.7 million number won’t be a record for long.

Further complicating the issue is the Edward O’Bannon case. In O’Bannon v. NCAA, former UCLA basketball standout Ed O’Bannon sued the NCAA over a violation of antitrust laws. He argued that because his UCLA likeness was still being used without compensation, the NCAA was treating him unfairly. In other words, UCLA should not be able to continue profiting from images of Ed O’Bannon in a UCLA uniform without O’Bannon receiving some form of compensation.

On Aug. 8, 2014, District Judge Claudia Wilken ruled in favor of O’Bannon.

The ramifications of this decision are as yet unknown. Surely, as a result of the O’Bannon decision, instances such as Johnny Manziel’s autographing controversy will eventually become a thing of the past. After all, it seems fair that a popular college athlete ought to make money off his or her own likeness without fear of losing his or her scholarship.

Unfortunately, we are dealing with a case wherein presumed equals are not at all equals with regard to their significance to the university as a whole. Particularly, there are 109.4 million reasons — roughly two-thirds of the entire UT athletics revenue production — why UT football players ought to receive more financial compensation for their work as opposed to other UT students and even other UT student-athletes. This is not at all to say that, among UT student-athletes, only UT football players deserve further compensation. Rather UT football players most deserve more compensation.

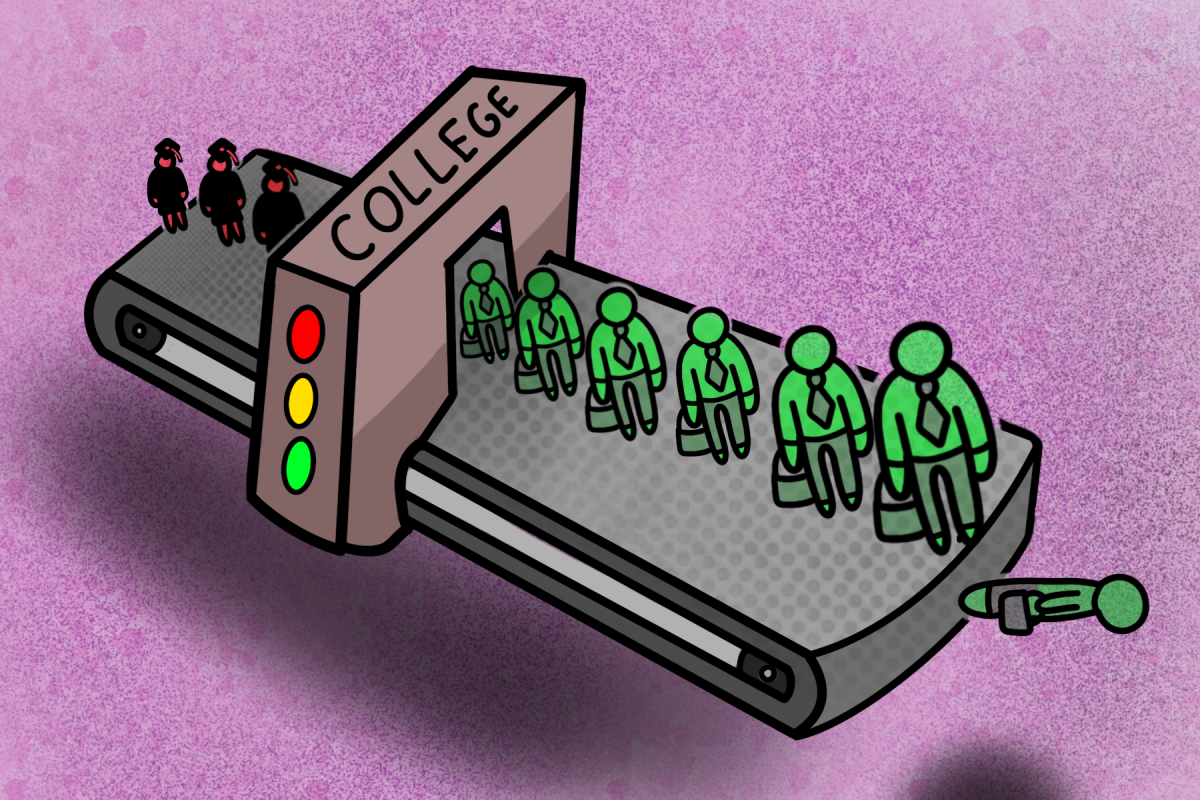

Considering the extreme amounts of money brought to the university directly from the football team, as well as the finding that Northwestern football players expended “50 to 60 hours of football-related work per week” during training camp, not to mention the “40 to 50 hours per week to football” during the regular season, it seems mostly unfair that UT college football players — and student-athletes from high revenue programs across the country — are not further compensated.

Which then leads to an even more controversial and complicated issue: What constitutes “further compensation”? Broader health care? Guaranteed, four-year tuition? A four- or five-figure salary? Or, more relevant to our own football program: Should players be able to accept free dinners from potential sports agents?

It is easy to understand why the notion of “pay for play” makes many uncomfortable. At the end of the day, students make a choice whether or not they want to be a student-athlete and are free to quit whenever they want. In this context, the current system seems appropriate, as a scholarship to many is payment in and of itself. But even this thought experiment is too simplistic. What if a player who could not otherwise afford to pay tuition decides to quit football and thereby loses his scholarship? What if a freshman football player on scholarship suffers a career-ending injury and his scholarship is revoked? For many players football is a choice and for many others football is the only choice, the only avenue to a college education and social mobility. For most, only the football-playing journey ends in college.

Among all these gray areas lies one glaring fact: the current system of scholarship-granting with regard to UT football players and college athletes as a whole (who help bring in a giant amount of their school’s financial pie) is inadequate. Instead of derailing what is becoming a more important issue each day with socially and politically charged words like “entitled,” “unionize” and “exploitation,” let us first ask ourselves whether that kind of temporal and physical devotion with that incredibly large amount of money on the line is fair without, at the very least, four years’ guaranteed tuition.

Sundlin is an English and radio-television-film senior from San Antonio.