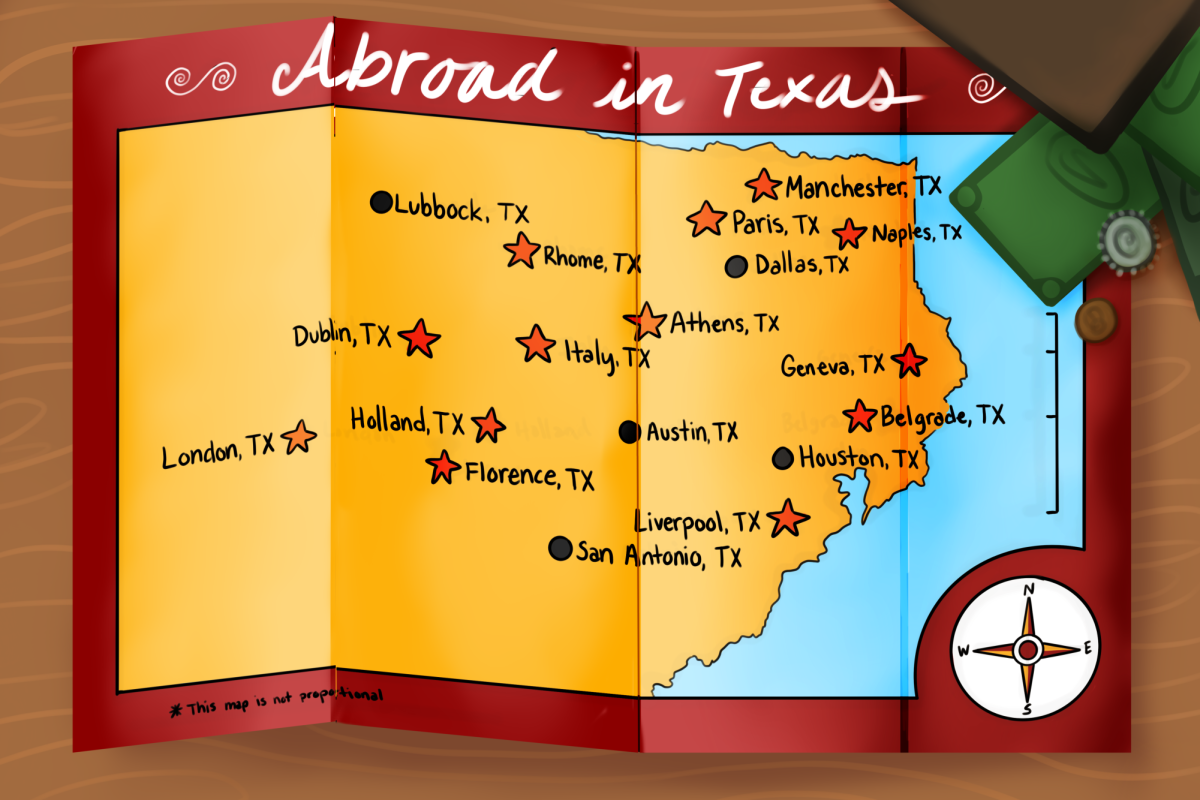

As observers of international affairs, we have a tendency to divide the world into good guys and bad guys, friends and foes. Old maps from the Second World War show the allied countries in one color, the axis countries in another. Cold War maps depict our allies in blue or white, the communists usually in red. Since Sept. 11, 2001, American policymakers have divided the world roughly between our friends in the war against terrorism, and those states that support or house terrorists (what former President George W. Bush infamously called the “axis of evil”).

Russia, under its dictatorial president, Vladimir Putin, poses a problem for these somewhat unavoidable colors on our maps. Putin’s actions in the last year have clearly shown that he aims to challenge American and West European influence in the territories around his state. Putin has invaded South Ossetia (formerly part of the republic of Georgia), Crimea and eastern Ukraine to prevent those regions from joining the European Union or the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, despite strong support in each nation for cultivating these Western connections. Putin has flagrantly vetoed efforts in the United Nations to punish Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad’s genocidal attacks on his own population. On July 17 paramilitary forces in eastern Ukraine operating Russian weapons shot down a civilian aircraft, Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, killing 298 civilians. Undaunted, Russia has continued to support this kind of reckless behavior, including provocative military aircraft flights near E.U. and U.S. borders.

Some observers have diagnosed a new Cold War, with a renewed division in Europe, but that exaggerates the Russian threat. For all his brutality, Putin is not seeking to close off Russia to Western capital, people or ideas. If anything, he wants his chosen allies at home to benefit from foreign investments, high-skilled workers, innovative technologies and modern media. Putin recognizes that Russian power and prosperity require integration, not separation, from global capitalist markets and knowledge industries. His goal is to manage Russia’s global integration for his maximum benefit, minimizing what he perceives as the advantages of the U.S. and E.U. Putin has shown little concern for the freedoms and living standards of his own citizens; his priority is the power of the state that he controls.

Condemning Putin as an aggressive tyrant is not sufficient, and it creates a self-fulfilling prophecy. Cornered and isolated dictators almost never back down; they usually turn to more threatening policies. Similarly, ignoring Putin’s misdeeds and hoping for the best in negotiations will not work, either. Aggressive and self-righteous tyrants seek to exploit opportunities; they will push against their neighbors until someone pushes back.

The challenge for American and European policy is to contend with the current realities and the likely reactions from Putin toward various Western actions. Many of our discussions of policy caricature our adversaries, while they simultaneously overstate our power and understate the range of our options. Like the simple lines and colors on our maps, our strategic vision of the world is much too simple. The key task for policy observers is to avoid dichotomies between good and evil and instead conceptualize how the United States can discourage Putin’s continued aggression without further antagonizing the Russian dictator by backing him into a corner.

What the United States needs is a policy that builds what former Secretary of State Dean Acheson called “situations of strength” while also offering Russia dignified exits from confrontation. Rhetoric about “stopping” Russia overstates our capabilities, and efforts to humiliate Putin make the resolution of conflict more difficult. Backing down is hard for everyone, especially political strongmen who rule through intimidation. Firmness, preparation and respect — even for brutal regimes — are key elements of a workable relationship. Political efficacy requires reasonableness in addition to moral indignation.

So what does a firm, prepared, respectful and reasonable U.S. and E.U. policy toward Russia look like? Historical experience points to three basic elements. First, the U.S. and E.U. should state clearly why we believe that Ukraine, Georgia and other countries around Russia deserve the right to join the E.U., NATO and other Western organizations if they wish. We must show consistency, seriousness and interests beyond immediate gains for our own societies. An adversary, like Russia, cannot appreciate our interests and values if we do not articulate them effectively.

Second, attention to Ukraine, Georgia and other countries does not mean that Russia should be ignored. Quite the contrary, U.S. and E.U. leaders should reach out explicitly to show that we value dialogue with Russia. We should give Putin reasons to want to do the right thing.

Third, and perhaps most important, Washington and Brussels must truly represent global opinion. Instead of falling into Putin’s trap of conceptualizing the conflict as a battle of the rich West against the rest, President Barack Obama and his counterparts must appeal to other major countries in East Asia, Latin America and Africa. Putin must see that there is little sympathy for his behavior around the globe. World opinion matters, and skillful diplomatic work to mobilize world opinion on behalf of democracy and national sovereignty is crucial.

Although the lines on the maps still matter, they should not force our thinking into rigid “us” versus “them” assumptions. Putin’s Russia is a threat, but it is a manageable threat. Policy leadership on this topic is more about diplomacy, negotiation and creativity than the moralistic rhetoric that dominates our public discussions. We can indeed help to lead the world without simplistically dividing it.

Suri is a professor in the Department of History and the LBJ School of Public Affairs. Follow him on Twitter @JeremiSuri.