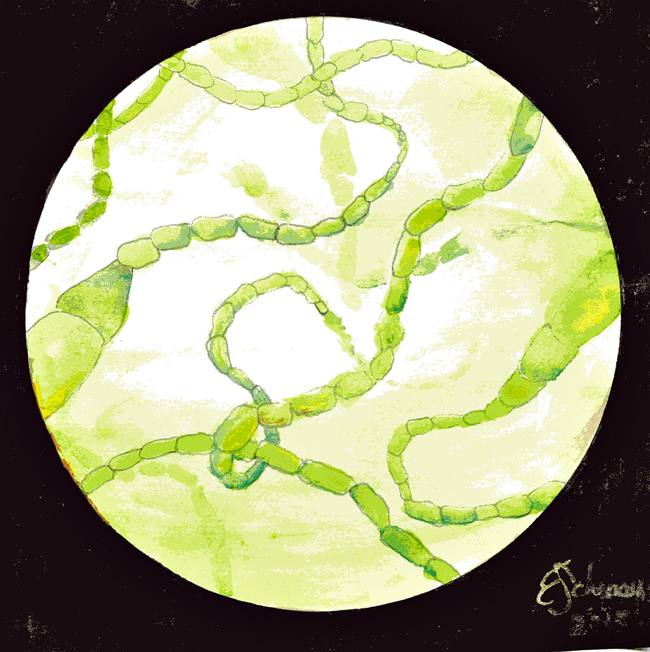

A strain of cyanobacteria, a bacteria typically found in freshwater, could potentially help lower greenhouse gas emissions, according to postdoctoral researcher and graduate student Jingjie Yu.

According to Yu, researchers in 1955 found a strain of cyanobacteria, called Synechococcus UTEX 2973, that can grow very quickly. The strain could potentially be planted outside of factories to counterbalance the effects of CO2 emissions, said Yu.

“The ability of cyanobacteria to use sunlight and CO2 to generate desired chemicals makes them the ideal biofactories for sustainable carbon negative production,” Yu said.

A biofactory is a type of natural incubator that uses plant matter or bacteria to give cells new functions, such as absorbing CO2.

According to Yu, cyanobacteria also have advantages as a biofuel, a type of fuel produced from natural organisms, when compared to other energy sources, such as ethanol or biodiesel.

“Cyanobacteria grow in various environments, and they are not food for humans, therefore, growing cyanobacteria and using them to produce biofuels will not create a debit between food and fuels,” Yu said in an email.

The cyanobacteria could accelerate the development of commercial applications in medicine or fertilizer of photosynthetic microbes, tiny organisms that use light to generate energy, according to molecular biosciences professor Jerry Brand.

Brand, who helped discover the strain, said the University is the only public source of this specific strain of cyanobacteria, and multiple scientists and technologists have shown interest in using it for their research.

“Another strain of cyanobacteria from this culture collection, Spirulina platensis, has been extensively exploited commercially for decades, although it grows much more slowly than the recently discovered strain,” Brand said. “Thus, we have every hope that thousands of acres of [the new strain] will be cultivated.”

Cyanobacteria is important because it started the Great Oxygenation Event, a major environmental change that started the production of oxygen in the atmosphere, neuroscience junior Viet Le said. The strain of cyanobacteria could potentially become more important in science if it can grow fast enough and has the potential to lead to further innovations in the study of sustainability, according to Le.

“I think it’s pretty amazing, especially considering that this bacteria is why life is able to thrive,” Le said. “It will be interesting to see how we can use nature as this kind of tool.”