Last Friday, UT celebrated the first black undergraduates to attend the university 60 years ago. The former students were honored for their courage and determination in the face of blatant racism, all while they led the charge for the integration of the student body in 1956.

But despite the celebration, it remains questionable if UT has honored their legacy. All these years later, and the UT student body remains largely white.

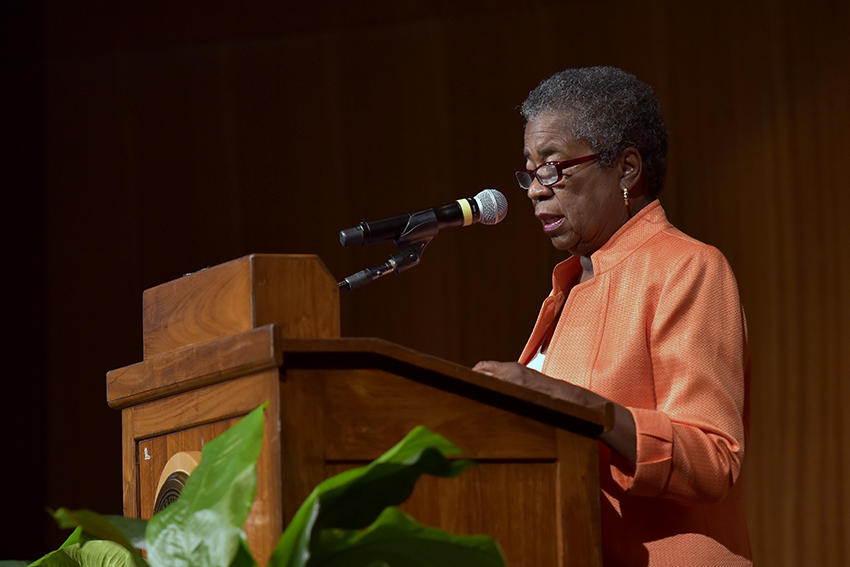

UT has remained, on paper, committed to promoting a diverse student body: recently, Fisher v. The University of Texas threw the university into the national spotlight for its defense of the race-based holistic admissions policy. In his address to the first black undergraduates, President Gregory Fenves acknowledged that barriers to equality in admissions at UT exist. He added, however, that “diversity and inclusion are top priorities for me at the university.“

And yet, black students make up only 3.9 percent of the student body, even though they make up 12.7 percent of Texas primary and secondary students. Likewise, 19 percent of the student body is Hispanic or Latino, even though they make up 53 percent of school children. On the other hand, white students are overrepresented, at 45 percent of the student body to the corresponding 29 percent of the overall Texas primary and secondary student population.

This racial imbalance is not entirely UT’s fault — it stems from the long history of segregation and discrimination in the United States. But if we’re going to claim that diversity and inclusion are “top priorities,” we as a university have an obligation to do more — beyond for the sake of “diversity” as an abstract ideal.

To start, UT can work to improve how welcoming it is to minority students who are already enrolled. While overt bigotry has more or less subsided since 1956, subtler forms of prejudice has replaced it. UT needs to continue to promote hubs for students of color and encourage programs that educate students on microaggressions.

Jasmine Barnes, a third year sociology student and the Director of Operations for Students for Equity & Diversity, wrote in an email that while she was prepared to come to an overwhelmingly white campus like UT, her experience at as a black student was considerably improved by finding supportive communities

“I was prepared to attend a university like UT where the black and African population was small, Barnes said. “While I think UT needs to do more to actively increase the racial diversity of its student body, I've been lucky to find communities like the Multicultural Engagement Center where I can feel affirmed and supported in my racial identity.”

Barnes mentioned that UT can become more open to prospective students by making the university more “financially accessible to students with identities that have been historically and systematically oppressed.” Because minority students are more likely to attend schools that have less funding and because household income is a large factor in whether a student completes their degree, extra help from the university is always welcome.

“We've come a long way since the first black students were admitted many years ago,” Barnes wrote. “The infrastructure that's been created to help encourage and retain minority students is huge. However, the feelings of isolation and ostracization for students of color are far from gone.”

The legacy of the first black undergraduates remains vital, and the incredible perseverance of those former students paved the way for all of the minority students who have followed. But we can honor them more by name on an anniversary — instead, we need to continue to battle to make UT even more open and even more inclusive than it is today.

Nemawarkar is a Plan II sophomore from Austin. She is a senior columist. Follow her on Twiter @janhavin97.