The end of my career started with lunch, the day after my great aunt’s funeral. I sat down in a booth on the right side of the old diner and looked out the window. The small town looked the same — it was inhabited by the same people over the last twenty years, and if anyone new moved in, it was only for the work and it would only take a year for them to wander off to a more exciting town. That’s what happens when you live in the suburbs, but I guess that’s why Great Aunt Ellie liked it so much. There’s a certain comfort in things staying the same. Things change so fast nowadays it’s hard to keep up.

The waitress brought me a cup of coffee and I looked out the window. A Ford Pinto rolled up through the parking lot and that could only mean one thing: Veronica was finally here. She was my cousin, and she got the car. We were meeting for lunch before she went back to college. I was staying in town for another week helping my sister go through Great Aunt Ellie’s things after the funeral.

Veronica was eight years younger than me. She had grown up as the baby in the family and I remember her being coddled and passed around by all my aunts and uncles nonstop. They all wanted to look at her and take some of her cute, loving, innocent baby energy and relish in it for themselves, because maybe her perfect youth would give them an extra year of life or something. Now Veronica was older, her hair was darker, and she always wore sunglasses, which I thought was obnoxious. Even at the funeral, she wore sunglasses right until she got up to the podium to deliver the eulogy. I figured she sat in the back or maybe even left right after because I didn’t see her at all until the reception.

“Hey, Veronica,” I said cheerfully.

“Hey,” she said as she plopped herself down on the opposite side of the booth. The waitress came by and offered her a menu, but Veronica shook her hands and declined, asking only for a coffee with half and half.

“Not hungry?” I asked.

"Nope,” she said. “I’ll be honest and say I’m kind of in a rush to get out of this shithole village before I contract a disease.”

One or two people looked at her disdainfully when she said that. I think she realized it and quickly pivoted to a different conversation topic.

“Anyway, Greg,” she at last took off her sunglasses to look me in the eye, “what did you want to talk about?”

It’s true, I had an agenda. When I heard the family writer would be coming, I had to make sure I got a chance to talk to her. Veronica was the only one of us who was making it—or at least trying to. She was getting an English degree at Stanford and was published once or twice in literary magazines or online somewhere. I forget which. I thought at least this would be a good networking opportunity in spite of the funeral.

“I’m writing a book,” I said.

“Oh?” Her eyes sunk a little bit.

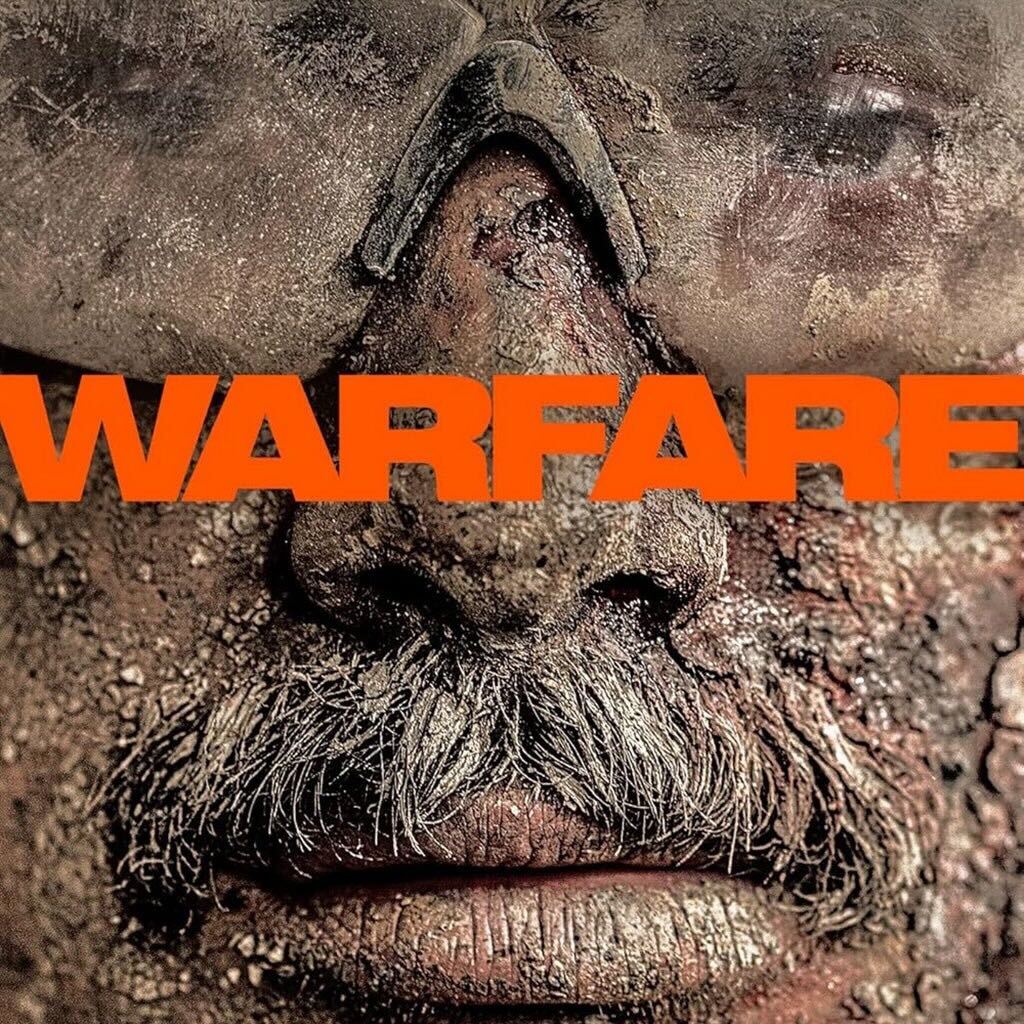

“Yeah,” I told her. “It’s about World War II.”

“Cool.” She stirred her coffee and took a sip. “I’m guessing you want me to look it over then or something?”

“Yeah, if you have time,” I said. I didn’t think this conversation would be so awkward, but here we are in this coffee shop, and for some reason I already feel sorry for mentioning it.

“How long is it?”

“120 pages right now, double-spaced. I’m almost done.”

She nodded. “Well, you know my email address. Send it over.”

She left a few bucks on the table for her coffee, said, “Later, Greg,” and left. I don’t know how she turned out to be such a prick, but I guess that’s what expensive schooling does to people.

***

So after I cleaned all of Great Aunt Ellie’s junk and went back home, I started writing every morning after I took the kids to school. I finished my manuscript and sent it to Veronica. The only note I got back was “Hey, Greg. I read your thing. If you’re serious about getting this published, let’s talk about it sometime,” and her apartment address.

After I talked to Becca, my wife, I emailed Veronica and made plans to go the following weekend. I flew in to California and was kind of hoping I’d get to meet a professor or someone while I was in town. I rented a car and drove to Veronica’s place. I’ll be honest, it was just a run-down apartment. The place looked like it needed a new coat of paint, and even then there wasn’t much going for it. I don’t know what I was expecting.

We sat on her crappy moth-eaten couch that she admitted was from Goodwill and talked over coffee. That is, she drank coffee. I didn’t because it was five in the afternoon and I wanted to be able to go to sleep at my usual time.

“So, Greg,” she said. “I have a few questions.”

“Ask away, I’m an open book, ha-ha.” She didn’t laugh.

“Why did you choose to write about World War II?”

“It just interests me,” I said. “Our grandpa had some pretty amazing stories.”

“But wasn’t he ten years old at the time?" she asked. "In that case, wouldn’t it have been better to write about the war from a ten-year-old’s perspective?”

I guess she had a point, but I didn’t have time for a rebuttal.

“Why do you want to write a book?”

“I, uh, I wanted to do something worthwhile with my free time and this seemed like a good way to spend it.”

She leaned back on the sofa and squinted her eyes like she was thinking hard.

“Why did you send me this manuscript?”

“I thought you’d know what to do with it since that’s what you’re going to school for and maybe you could help me send it to the right person.”

“Have you read any of my stuff?” she asked. Now I was embarrassed.

“Um, no, but I would if you sent it to me! A read for a read, right? Plus, your eulogy was outstanding. I was impressed. A beautiful tribute to Great Aunt Ellie.”

She put her hands on her eyes and rubbed them down her face before slapping them on her lap.

“You wanna know something?” she asked.

“What?”

“Great Aunt Ellie was a shitty person. And worse than that, she was boring.”

“I beg your pardon?”

“She was sweet, I guess, in the sense that she wouldn’t stop shoving homemade sugar cookies down people’s throats, but she was racist and she did almost nothing with her life other than sing in the church choir and give birth. RIP. But do you want to know why the eulogy was good? It made people miss a selfless woman with a tragic illness.”

“You don’t believe that about Ellie?”

“Of course not. The whole thing was a lie.”

I was confused by this weird tangent, but I let her continue in hope that I might get some answers.

“I exaggerated everything so it would make people forget that she was rude to almost everyone in the last decade of her life. She thought the year was 1990 and starved her cat to death because she forgot she had one.”

That was true. We had found Aunt Ellie’s cat in the laundry room, stiff as a board next to the food bowl.

“But what does that have to do with my book?” I asked.

“Your book is nothing. It is nonsense. It’s not a lie because there isn’t any truth to it to even make it a lie. Plus, the story’s been told before.”

I got extremely defensive. “If you didn’t like it, why did you tell me to come here?”

“Chillax, Greg.”

Chillax. I’ll never forget that. My plane ticket cost at least an entire week of my wife’s salary but this kid is telling me, “Chillax.”

“It’s not a big deal,” she said. “You can write books that are similar to each other. What I’m saying is you have to make it hit the right chords. Make the feelings different than anything else. Ever read Slaughterhouse Five? Your book is a watered down, crappy version of Slaughterhouse Five. But Slaughterhouse Five is just a less funny version of Catch-22.”

“What are you getting at?”

“Nothing under the sun is new, or whatever the saying is,” she said. “This conversation that we’re having now, even though it’s happening in real time between me and you, probably already exists in literature somewhere.”

“Are you on drugs?”

“Listen, Greg. We’re just two people, talking about a crappy manuscript, and this SCENE that we are LIVING IN probably already exists as a draft on someone’s crappy, Bukowski-wannabe’s shitty laptop. Or it’s been written by Shakespeare already since everything is. What I’m getting at is there are no new ideas. Don’t humor yourself by thinking you’ve got some novel idea. Originality is a sham that you have to fool people into believing by using flowery language and chutzpah.”

“So you’re saying my manuscript is unoriginal?”

“Greg, I’m saying not only is it unoriginal, but it’s not written in a way that makes me get past the unoriginality. You have no flavor. You’re just a unfulfilled white guy with time on his hands, a laptop, and evidently, jacking off isn’t good enough for you.”

I stood up and made my way to the door.

“But you want to know what it takes to be a writer, right?”

I stopped. I didn’t come all this way for nothing, and if it meant indulging in Veronica’s psycho lecture about “writing,” I guess that’s what I signed up for.

“Yes.”

“Follow me.”

***

She led me down the hall and opened a doorway that led to the most disgusting room I’ve ever seen. The floor wasn’t visible from beneath the piled-up laundry, old plates of food, and what I’m guessing were class assignments. I didn’t even realize it was an actual human’s private bedroom at first until she said:

“DO YOU SEE HOW I LIVE, GREG?”

She flicked on the lights and I swear to God a rat scurried under a pile of papers by her nightstand. The nightstand itself was littered with empty water bottles and half-drank cups of coffee. I couldn’t help but wince.

“I haven’t cleaned since August in 2016. I haven’t slept for more than four hours in the past month and a half. Do you know why?”

“Because you are mentally unstable?”

She kicked a path out of the garbage on the floor and wandered toward the closet.

“Because I’ve been writing instead. And when I’m not writing, I’m reading. And when I’m not reading, I’m editing. And you know what, Greg? That’s how I got all three of my puny published works published. THAT’S HOW, Greg. You have to let it CONSUME you until there’s nothing left! And then you get rejected! Rejection after rejection, can you handle it?”

“Well, I think so!”

“Do you know why I love writing, Greg?”

She was rummaging in the closet for something, tossing old shirts, CDs, and all kinds of junk aside in her mad search for whatever it was she was looking for until, finally, she pulled a gallon of gasoline out from the closet.

“Wha-what are you doing?” I stammered.

She doused the gasoline all over her pile of laundry in the middle of the room.

“Veronica—”

“I’m the one who gets asked to write history!” Now she was pouring it on the unmade bed in generous portions.

“I write the eulogies,” she said. “I have the final say. Even if my own family only contacts me to write for them when someone dies, or only wants me to read their crummy manuscripts!”

“Veronica, stop!”

She emptied the can over the entire room. All over the assignments, the dirty dishes on the nightstand, the walls, the poor family of rats hiding in the corner. Everything.

“Whatever anyone says to me, whatever anyone has ever done to me, I get to write it down and that’s how it gets remembered. And you know what my advice is, Greg?”

“What?” I screamed.

She pulled a matchbox out of her pocket and held a lit one between her fingers.

“Get out while you can. Find a better life before it’s too late.”

***

I ran out of the apartment before she had a chance to drop the match. I don’t think she ever did because I wasn’t asked to write anything for her funeral, being the next-in-line writer in the family.

Before I left Stanford, I went by the English department and this old guy, a professor, let me show him my manuscript. He was really nice about it since I told him Veronica was my cousin. Turns out she was one of his students.

A month later, the old guy got back to me though and said my book was too much like Slaughterhouse Five. Plus, it lacked flavor.

I don’t think I’m cut out for this lifestyle.