Depression and stress have been studied for the psychological effects they have on the human body, but doctors are now looking at how the disease can affect the immune system.

The Immune System, Stress and Depression Study is being conducted by Dr. Marisa Toups and Research Associate Alyssa Marron in the Department of Psychiatry at Dell Medical School. They are studying the link between depression and the observed increase of the proteins cytokines and C-Reactive Proteins (CRP), which are used by the immune system. This increase shows that some depressed patients may respond differently to stress than is expected.

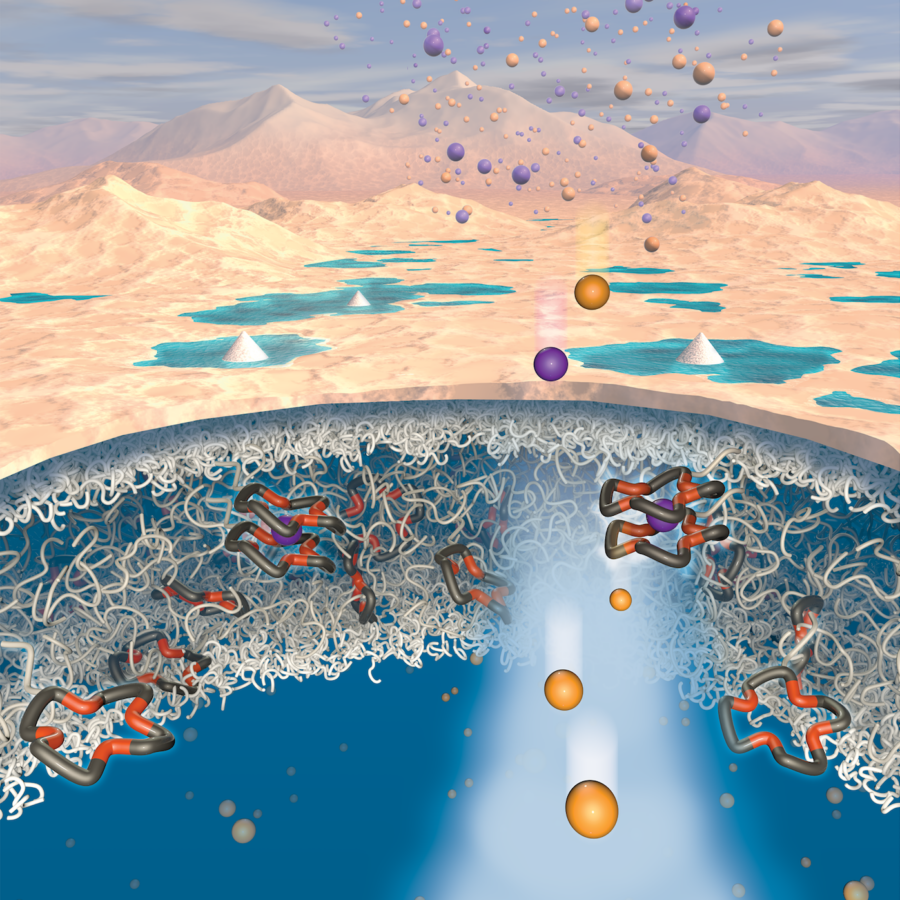

Inflammation is part of the immune system’s response to harmful foreign particles called pathogens, said Gregory C. Ippolito, a research assistant professor in molecular biosciences who is not part of the study. Cytokines and CRPs are two of many proteins, called inflammatory markers, which are involved in this immune response, Ippolito said.

CRPs are produced by the liver and they destroy certain bacterias, Ippolito said. Cytokines refer to a series of signaling proteins and they help regulate the inflammatory response by signaling to either extend or end it.

Generally, it’s best that the inflammatory response and increased levels of CRPs are acute, meaning that they last for a short period of time, Ippolito said.

“If the response is not acute, and inflammation is chronic (lasts for extensive periods), it shows that there is an issue in the body that the immune system can’t resolve,” Ippolito said.

Many patients with depression show increased levels of CRPs and cytokines for longer periods than normal, Toups said.

“Through the study we want to understand why this prolonged elevation of markers occur, and if it is related to the patient’s (bodily) response to stress,” Toups said. “We also want to characterize if there is a subgroup of patients (with depression) who have this problem.”

Each patient is examined in a two-day process, Marron said.

“On the first day, the participant does a blood draw, so we can measure CRP levels … an interview, and questionnaires, which help in assessing patients.” Marron said. “On the second day, the patient takes computerized stress tests. After the test we take the patient’s vital signs and saliva samples to see if cytokine and stress hormone levels changed during the test.”

The researchers want to see if stress during the test causes certain people to have elevated levels of inflammatory markers and if this may be related to why they are depressed, Toups said. The broader goal of the study is to see if CRP levels in blood can be used as a predictive variable.

“(We want to see) if CRP levels can predict the symptoms a depressed patient will have, and how inflammatory their response to stress is,” Toups said.

If the study helps to uncover the role of the inflammatory markers in depressed patients, it may also alter the types of treatments, Toups said.