This coming week, thousands of UT students will return to their hometowns for Thanksgiving. Some of them will return to family members, freshly cut Christmas trees, close childhood friends, dusty holiday decorations and a sense that, in spite of the stress of midterms, finals and an increasingly contentious political landscape, everything might be OK.

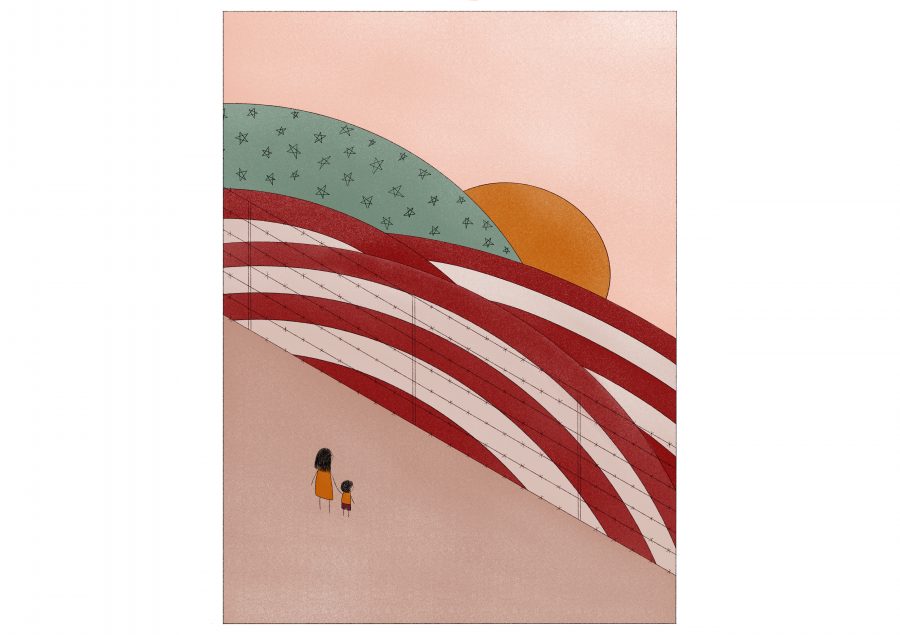

Other students will return home to absent family members, barbed wire and armed military, militia and law enforcement. While it sounds like a war zone, that’s not where these students live. These students live in Texas, just south of San Antonio, and I’m one of them.

In spite of the increased national discourse surrounding immigration enforcement along the United States-Mexico border, and polarizing talk of an immigrant “invasion,” this issue is close to home for many students at UT. Before students form judgments about militarization along the border, they should first talk to their classmates who may be directly affected by it.

Oscar Corpus, an English junior from McAllen, Texas, expects the recent militarization of the border to affect his ability to see his family members.

“I used to celebrate Thanksgiving (in Mexico),” Corpus said. “And I say used to because this year I’m probably not going to cross the border because it’s becoming heavily militarized. What if something happens and they close the border, and I can’t come back to school? There’s that danger of if I leave, I’m never coming back even though I’m an American citizen.”

For undocumented students, returning to border regions is even riskier, as increased immigration enforcement has the potential to jeopardize their status.

Jesus Acosta, an advertising graduate and formerly undocumented student, remembers the anxiety associated with traveling home to the Rio Grande Valley for the holidays. Going home to the RGV means traveling through the Falfurrias, Texas, checkpoint, a daunting task for undocumented students. Acosta recalls the fear of crossing the checkpoint, guarded by dogs and armed border patrol agents just to see his parents.

“I can only imagine what it’s like now,” Acosta said.

Clearly, this issue isn’t strictly political. Kevin Barajas, a government freshman from Brownsville, Texas, leans conservative on many issues but said he worries that the national narrative surrounding this issue fails to include the stories of border residents who will have to work during the holidays. Customs and Border Protection is a major employer for residents of border towns, with more than fifty percent of agents identifying as Hispanic or Latinx.

“A friend of mine’s father, who works for Customs and Border Patrol had to tell his kids, ‘Hey I can’t be there for all of Thanksgiving, and maybe Christmas, because they’re sending me to California,’” Barajas said. “I’m sure he’s not the only one who has to be relocated. They can’t be with their families during the holiday.”

Regardless of how this issue will affect students returning home to border towns this upcoming week, national discourse fails to demonstrate the real impact of border militarization. Corpus was saddened by news of the border’s militarization, but not surprised.

“They treat (the Rio Grande Valley) like a whole separate entity — a buffer zone between the two countries,” Corpus said.

But we’re American, too. So before forming judgment — ask us what we think. We’re your classmates, and we have a lot to say.

López is a rhetoric and writing junior from McAllen.