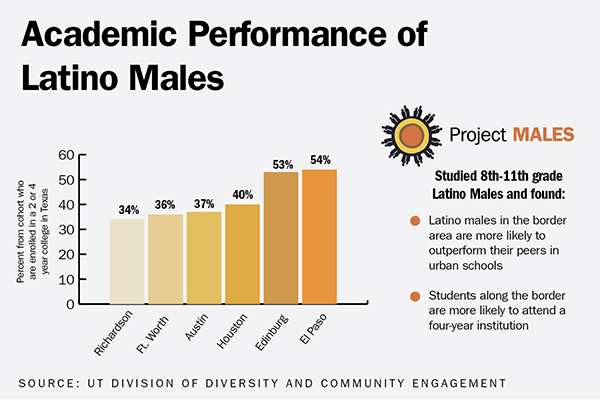

Latino males along the border are more likely to attend college post-graduation compared to those living in urban areas, according to the first policy brief by Project MALES (Mentoring to Achieve Latino Educational Success), a UT initiative based within the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement. The study, released in early March 2019, uses data from the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board and the Texas Education Agency and tracked students from eighth grade onward, focusing on Latino and black males.

This disparity may be due to the generally higher amount of dual-credit courses along the border region, said Emmet Campos, director of Project MALES.

“The border regions have a really strong dual-credit early college high school program and initiatives, and we think it may have something to do with that,” Campos said.

Another factor may be that teachers along the border may be more understanding of students’ situations, said Rodrigo Aguayo, program coordinator of Project MALES’ mentoring program.

“Many students grew up in the Valley … and then stayed there,” Aguayo said. “So these teachers understand where the students are coming from.”

Students may be less likely to pursue higher education in urban areas because they tend to be a minority there, said Israel Vasquez, who is from Dallas and works with Project MALES to mentor Latino children in nearby public schools.

“At the border, our culture is … celebrated and is a known part of our lives, whereas in urbanized areas, that integration … isn’t really there,” biology sophomore Vasquez said. “It’s almost like a clash of ideals … which causes dissonance within the classroom.”

In addition, there is usually less community support for Latinos in urban areas, said Kathy Estrella, who is from a border town and works with the program.

“There’s already this feeling of community and more support (along the border),” said Estrella, a sociology and Chinese sophomore. “If you go to the schools over here, the students don’t feel really like they belong.”

Vasquez said this might, in turn, discourage higher education.

“Because of that dissonance, (Latino students) end up not liking school a lot and think, ‘I don’t want to do this again for four more years. This is torture,’” Vasquez said.

Spanish junior Oliverio Castanon works alongside Vasquez and Estrella and said the program serves an important purpose.

“Usually the only supporting voices that come for us was our family,” Castanon said. “But even then, some kids don’t have that supporting voice … and that’s ultimately why we’re there.”