Universal Classic Monsters is back from the grave yet again, this time with horror powerhouse Blumhouse behind the wheel.

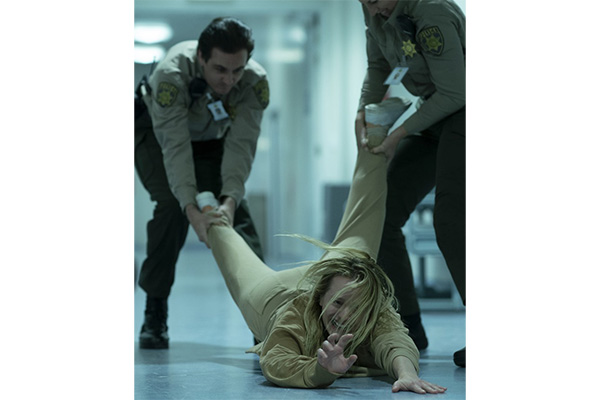

“The Invisible Man,” directed by Leigh Whannell (“Upgrade”), is a reimagined interpretation of the eponymous novel by H.G. Wells. “The Invisible Man” is not a story focusing on the man himself, but a nail-biting experience following a powerful woman’s fight to break free from an abusive ex-partner. The film explores the concept of mentally and physically escaping such a relationship, combined with the uncertainty of knowing if leading character Cecilia’s (Elisabeth Moss) abuser is physically in the room with her.

Elisabeth Moss is a show-stealer in the leading role of Cecilia. Her intense and torturous reactions to the taunting from the title character are equally as heartbreaking as they are terrifying. She truly conveys the deep emotional stress her character is facing, causing audiences to heavily sympathize with her. The few scenes without horror provide a look at her Cecilia as she expresses genuine thoughtfulness and care to her supporting characters. This only helps involve the audience in the various aspects of her character’s personality.

Aldis Hodge is fantastic in the role of James, offering comedic and heartfelt support to Cecilia throughout the film. His well-timed line deliveries and calm mannerisms evoke a sense of calculated safety around his character. His on-screen daughter, Sydney, played by Storm Reid, has an equally infectious personality. Her expressive and quirky attitude provides a great contrast to the intense horror of the film.

Whannell directs the camera with the intent of pure suspense. Because the antagonist of the film is literally invisible, mundane things such as empty chairs or rooms are immediately filled with unease. On frequent occasions the camera will pan to the side of a character, emphasizing what may or may not be inhabiting the empty space. This results in moments of great tension, such as one where the camera pulls away from Moss’s character to the “empty” space behind her. The audiences become just as much of a victim to the paranoia the invisible man causes as Cecilia is.

The cinematography, set design and color grading mainly revolve around murky grays, dense blacks and sickly whites. While its not exactly visually appealing, it certainly works to cast a frightful visual style over the film. As Cecilia’s dilemma worsens, the visual style of the film becomes a bright and isolating white. The contrast of a brightly lit and visible atmosphere with a foe who is invisible is quite effective.

While a core dilemma of the film is that most of the characters refuse to believe Cecilia’s claims of her invisible assailant, the constant repetition of no one believing her can be a bit tiresome. For the majority of the film, the audience and Cecilia are the only ones aware of the existence of the Invisible Man, so it is quite frustrating to watch other characters refuse to believe her story for almost half of the film. It is understandable that the filmmakers wanted audiences to feel the same helplessness as Cecilia, but after a certain point, it becomes repetitive. The thematic elements start to hinder the enjoyment of the film, leaving the audience tired. The film would have benefited from a slightly shorter run time. Luckily, a jaw-dropping twist breaks the film out of this midway flunk.

Despite some length issues, “The Invisible Man” is a solid and timely re-interpretation of a classic horror tale.

3.5 “he’s still alive”'s out of 5