Navigating the Speedway bricks alongside their owners, service dogs are often working from 8 a.m. classes to late night study sessions at the Perry-Castañeda Library.

The work that service animals do is an important part of their owners’ everyday lives. Despite this, students with service animals say others often misunderstand the difference between working animals and pets.

While marketing senior Emeline LaKrout has been blind her entire life, she only used a cane for several months during her freshman year, which she said frustrated her. After one of her friends got a service dog, she said she began researching the possibility. The summer before her sophomore year, she was matched with her first guide dog, Vega.

“A cane is a metal stick, so it’s dumb,” LaKrout said. “It can’t find doors for me or little things (Vega) can do.”

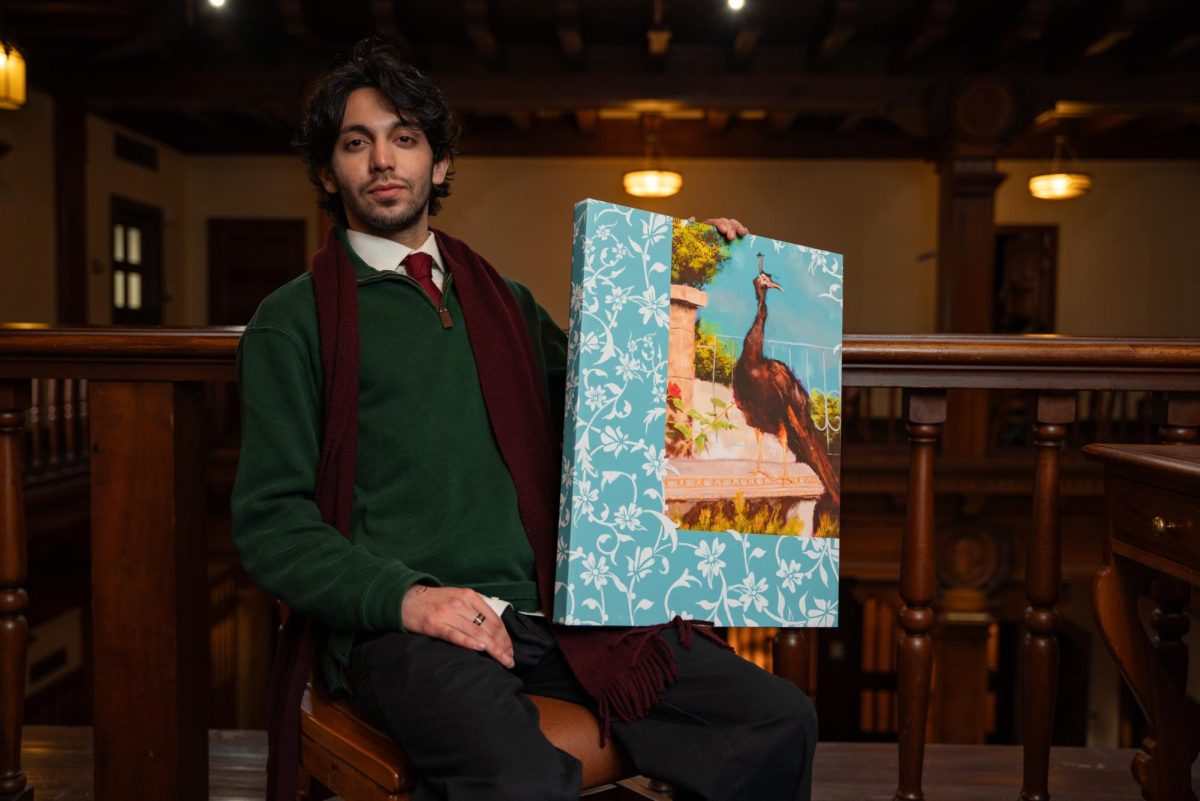

Government senior Archer Hadley got his first dog, Pepe, during his freshman year. Often, students don’t realize Pepe is always working, even when he’s walking beside Hadley’s motorized wheelchair, and Hadley isn’t giving him direct commands.

“(Service dogs) are an extension of the person and their needs,” Hadley said. “We are meant to be unified. Sometimes people view him as a pet that I just want to bring to school.”

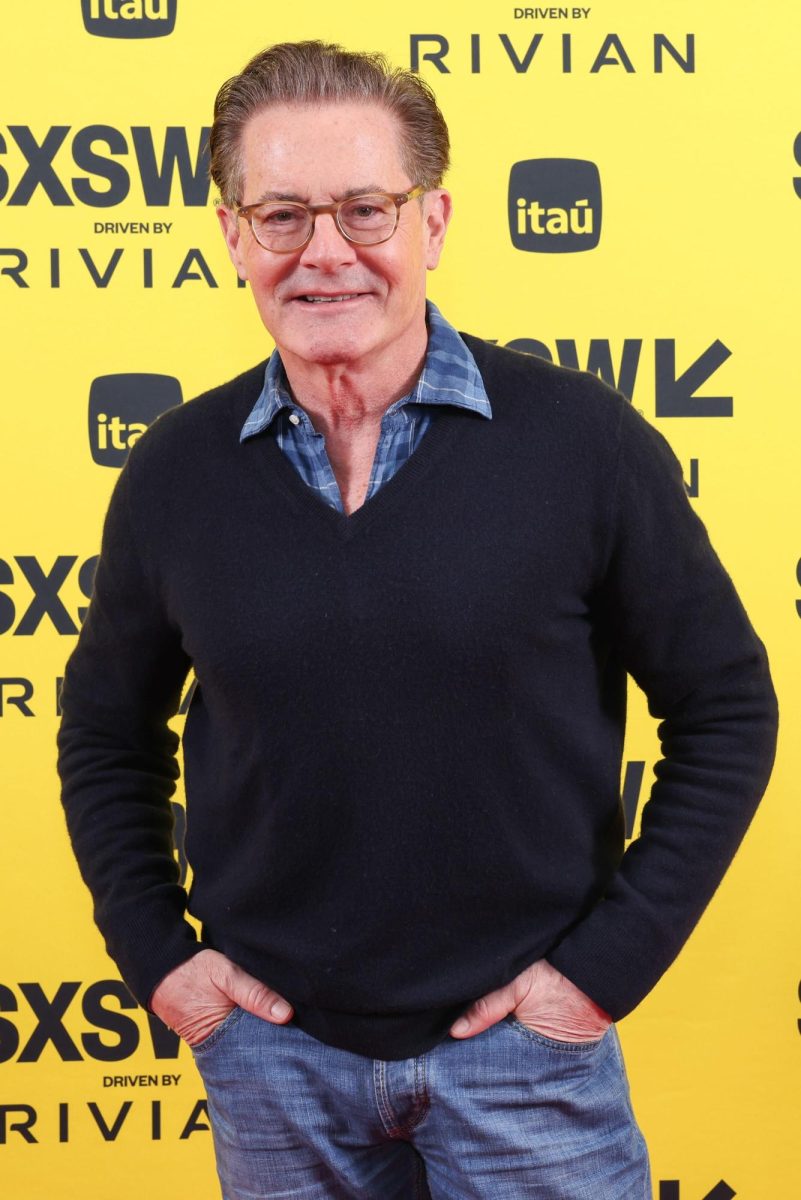

Maeve Cooney said she began training service dogs for the Canine Companions for Independence program when she attended graduate school at UT in 2002. 18 years later, Cooney is the senior chemical engineering administrative associate and has trained 13 dogs.

“The reason that we raise these dogs is so that they can help someone and make their life easier and better,” Cooney said.

When students bring their pets to campus, sometimes under fraudulent service animal documentation, Hadley said it makes accessibility harder for students who need service animals to navigate campus. He said a student once asked him where he got Pepe’s service animal vest and if he could purchase it from Hadley to use on his own dog.

LaKrout said animals without proper service dog responsibilities and training potentially damage the service dog image.

“People bring pets on campus, and those dogs can be very distracting and intimidating,” LaKrout said. “I’ve had multiple untrained dogs bark at (Vega). (They) might genuinely ruin a service dog that provides a vital service and ruin the experience for the rest of us who have very well trained animals.”

When walking by students on campus, Lakrout said she prefers for people to ignore her dog. But students will sometimes pet Vega without permission and will even address her dog instead of her.

“People will ask my dog how her day was, what her name is, how old she is,” LaKrout said. “I don’t think I’ve ever had anybody ask me what my name is. It’s like you don’t exist anymore.”

Hadley said he enjoys the social interactions having Pepe on campus invites.

“In terms of self-confidence, social confidence and people wanting to come up and interact with me, (Pepe is) a huge benefit,” Hadley said.

Despite their formal training marked by a service vest, students with service animals said they often have to explain the credentials and importance of their dog’s responsibilities in mitigating a disability to others.

“When you see a dog in a kind of harness, it’s pretty clear they’re working,” LaKrout said. “That’s not just a pet, that’s a service dog, and it’s working, and it’s trying to focus and take care of its owner.”