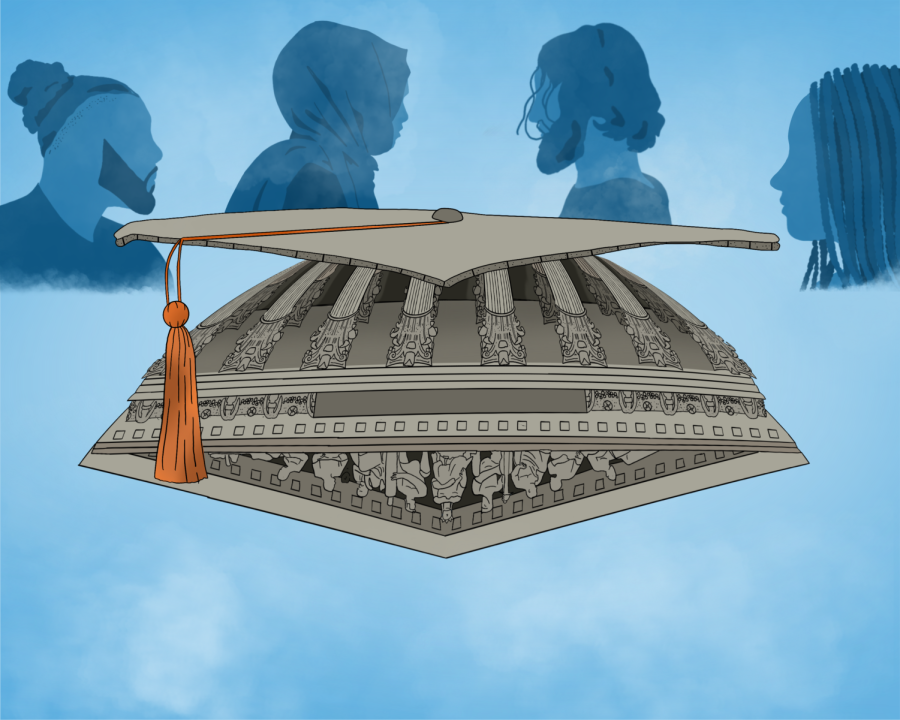

Minority students deserve UT’s support after ban on affirmative action

July 3, 2023

Diversity efforts in higher education continue to face constant attacks. Following the eradication of DEI offices in public universities in Texas, students from marginalized communities feel isolated as it is. Now, with the ban on affirmative action, many wonder why their educational qualifications are being scrutinized.

Last Thursday, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that the use of race in college admissions violates the Equal Protection Clause. This decision means that universities across the country, including UT, can no longer consider race as one of many factors when admitting students.

In the ruling, Chief Justice John Roberts said that despite the ban, students may still discuss “how race affected his or her life, be it through discrimination, inspiration or otherwise” in their college essays. This creates an opportunity for admissions officers to better understand an applicants’ background and what that student can bring to the university.

We acknowledge the Grutter v. Bollinger ruling said that affirmative action was not a permanent solution. However, we disagree with the decision to get rid of race-conscious admissions without a feasible solution. Affirmative action has persisted because universities have not found an alternative admissions process that replicates the diversity in the surrounding areas of the institution.

In 2008, Abigail Fisher sued the University of Texas system after UT denied her admission. She claimed that her academic record exceeded that of minority students admitted into the school that year. The case, Fisher v. University of Texas, was ultimately heard by the US Supreme Court once Fisher appealed the decision. The Court found that UT’s use of race was narrowly tailored enough to increase educational diversity, which benefits all students, without discrimination.

The editorial board wants to make one thing clear: students of color are not “taking” spots from anyone. They worked hard to get where they are. UT’s admission process is holistic and extremely complex, and race is not the determining factor. It’s ignorant to assume anyone is owed a spot to begin with.

“UT will make the necessary adjustments to comply with the most recent changes to the law and remains committed to offering an exceptional education to students from all backgrounds and preparing our students to succeed and change the world,” said the University of Texas in a statement.

Regardless of the ruling, the University of Texas has a diverse campus, and it must work to grow and maintain it.

Without affirmative action, racial diversity at universities will likely decrease. Following the ban of race-conscious admissions 16 years ago, the University of Michigan’s Black student enrollment dropped by 44% while Indigenous enrollment dropped by 90%. The University of California system also saw a disproportionate decline in Black and Latino enrollment.

“Ultimately, fewer students of color are completing a certificate or degree, which is sort of a college microcosm of society at large,” said Ryan Fewins-Bliss, executive director at Michigan College Access Network, which helps low income, first generation and students of color pursue and complete their higher education goals. “If those folks aren’t able to access college…we’re not able to give businesses what they need to be successful.”

Michigan schools have actively tried to bring in students that have diverse backgrounds through new recruitment tactics.

“None of it is working as well as affirmative action in the admissions and enrollment process,” Fewins-Bliss said.

For Texas, the “Top Ten Percent Law” still stands. It grants all students in the top six percent of their class admission to UT, and has been regarded as a race-neutral policy. However, with the recent ban of race-consideration in admissions, there is no longer enough support for underserved prospective applicants outside of the top six percent.

Ultimately, the students that will feel the brunt of this ban’s effect are minorities from lower-income communities. Underserved student populations have less access to resources that would pad their resume for college, including SAT preparation courses, money to fund athletic endeavors and private college counselors – all of which are regular practices for families with the financial means to pursue them.

According to a study done by The Brookings Institution, a racial gap in SAT math scores persists. Black and Latino students average scores of 428 and 457 respectively, compared to white students who score an average of 534.

“Given everything we know about the relationship between socioeconomic backgrounds and access to academic resources, whether (it be the) school you attend, private tutoring and college admissions counselors, rich kids have a leg up in the college admission process,” said

Matthew Giani, Research Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology and interim director of the Texas Behavioral Science and Policy Institute at UT.

In order to level out the playing field for those without the means to pay for standardized test tutoring, the UT Office of Admissions should permanently offer a test-optional admissions process.

Most of the time, students from underserved backgrounds do not see themselves attending a prestigious university. Now more than ever, UT should place a greater focus on recruiting racially and economically diverse students by informing them of the resources available at UT, such as the Texas Advance Commitment.

“I think all students are affected by this ruling because it relates not just to access for students of color, but also the quality of education for everybody,” said Liliana Garces, a professor at the UT College of Education.

While affirmative action was the most equitable solution, now that it is gone, UT needs to find a way to retain the diversity it has worked so hard to gain. Advocating for underserved students makes higher education more accessible for everyone. All students at UT are qualified to go to this university, and minority students are no exception.

The editorial board is composed of associate editors Ava Hosseini, Sonali Muthukrishnan and editor-in-chief Lucero Ponce.