The Food and Drug Administration approved the first-ever vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus, which uses breakthrough research by a UT professor.

Molecular bioscience professor Jason McLellan worked with a research team at the Vaccine Research Center at the National Institutes of Health to develop a new way of designing vaccines to treat RSV in 2013. McLellan and his colleagues’ research was used in the development of multiple RSV vaccines getting approved this year, including Pfizer’s vaccine for maternal immunization the FDA approved on Aug. 21.

RSV is a highly infectious virus that circulates every winter season, causing infections like bronchiolitis, said Dr. Barney Graham, professor at Morehouse School of Medicine and McLellan’s colleague in the vaccine research.

It is the leading cause of hospitalizations for children under five years old, McLellan said. He also said RSV can be deadly to the elderly.

“It causes a lot of disease at the extremes of life, and in between you get repeatedly infected but don’t have a lot of severe ailments,” Graham said.

McLellan said most work on vaccines has historically not relied on much information about the molecular features of a particular virus.

“The earliest vaccines, you just had to grow up the pathogen, virus or bacteria, inactivate it, weaken it, inject it and hope that worked,” McLellan said. “You didn’t need to know anything about which proteins are on the surface.”

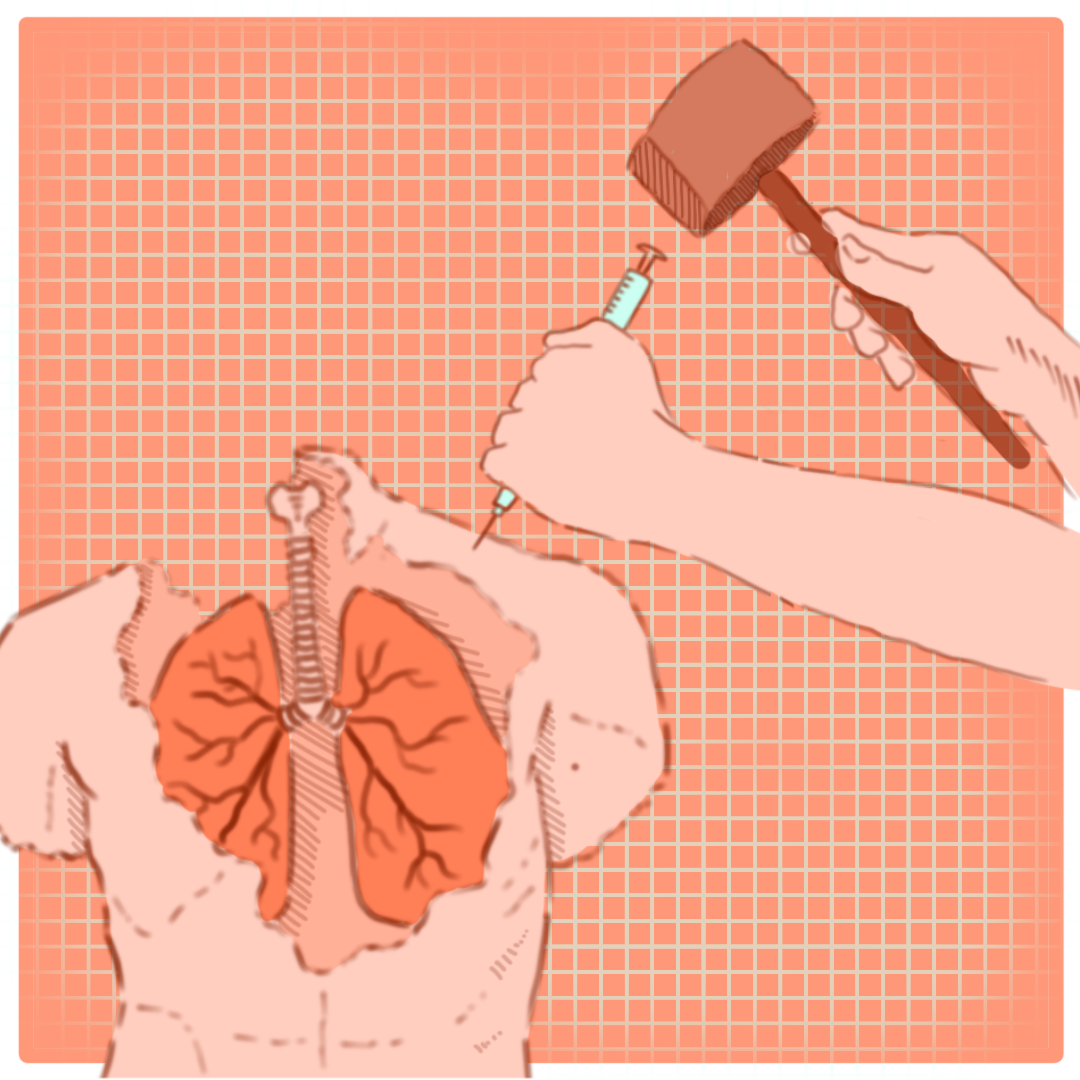

McLellan said an RSV vaccine using the traditional approach failed in the 1960s, and decades of research since then showed that RSV required an approach that took the virus’s unique structure into account, leading the team to develop structure-based vaccine design.

McLellan said the researchers took a rational, engineering-style approach, starting by isolating thousands of antibodies from people who survived infection to determine which ones most effectively neutralized the virus. After gathering the best antibodies, McLellan said his lab used structural biology to identify where antibodies bound to the protein on the virus that causes infection.

“We create a three-dimensional map of the viral surface protein and all the antibodies that bind (to it), and then we use protein engineering to make changes, substitutions, optimizations to the viral protein,” McLellan said. “(When) we inject it (as a vaccine), it will elicit those best-in-class antibodies.”

McLellan and Graham’s research was used to create the first RSV vaccines for people over 60 and a vaccine for maternal immunization, which will immunize pregnant people in their third trimester and provide enough antibodies to protect their infants until they are six months old.

“Vaccines cost a certain amount, but the amount of severe illness, hospitalizations, deaths that it’s going to prevent will far outweigh that,” McLellan said. “We’re going to hopefully be protecting the very old and the very young.”

Graham said the structure-based vaccine concept behind their research has also been applied to make more effective vaccines for many viruses in addition to RSV, including COVID-19.

“RSV has often been dismissed or ignored as a thing that people didn’t work on very much,” Graham said. “But (it) turns out that RSV has helped lead the way for this whole new way of thinking about vaccine design.”