Editor’s note: This story is the fourth in a series exploring race, racism and diversity on the UT campus.

In March, a racially offensive cartoon commenting on the media’s coverage of the killing of Florida teenager Trayvon Martin motivated members of the University community to picket The Daily Texan and shined a spotlight on the coverage of race by the Texan in the modern era.

Journalism professor Robert Jensen said the most recent controversy at the Texan is the latest in a long line of incidents.

“These flashpoints at the Texan seem to pop up fairly frequently,” Jensen said.

The Texan has been the student newspaper of UT since 1900 and is a quasi-independent entity of the University, overseen by both the office of the vice president of Student Affairs and the Texas Student Media Board of Trustees. The editor-in-chief is elected by students and the paper is funded by revenue from advertising and student fee allocations from the Student Services Budget Committee. The policy of a University official monitoring the paper’s content was established in 1936 and was inconsistently enforced until 1971. In 2007, this policy of prior review was abolished after 36 years of use.

For the first 30 years of the Texan’s existence, it’s difficult to find an indication of a stated political stance the University held on segregation. Laden with details of campus celebrations and ceremonies, the Texan focused more on student life than state news or major issues.

The paper gradually grew to include news of a more serious tone in the ‘30s and ‘40s. The Texan openly voiced racist sentiments, including the publishing of a January 12, 1940 guest column in The Cavalier Daily, the student newspaper of the University of Virginia. In the column, the editorial board argued that pending anti-lynching legislation was a ploy by Republican lawmakers to garner more African-American supporters.

“Congress cannot legislate away the threat of mob violence with this ridiculous bill,” the editorial said. “Only education and enlightenment, directed by the thinking men of the South can wipe out the evil. It is our problem as a state, and if you look at the record, you will see we are doing a pretty good job. Let the Congressmen find some less distasteful method of garnering votes.”

Over the next 10 years, the push for integration grew stronger, and by the time Ronnie Dugger became editor of the Texan in 1950, publishing pro-integration editorials reflected the changing campus climate. Dugger, now an 81 year-old journalist in Austin, recalled the state of integration in an interview.

“The position at the University was that there would be no blacks there,” Dugger said. “This was 1950-51. Blacks were not welcome. I was, of course, for integration at The Daily Texan,” Dugger said.

Dugger said his election as a progressive editor of the Texan was a result of student support for integration on a campus where the University administration was kept from taking a pro-integration stance by ties to the legislature.

“You have to remember [the legislature was] literally for segregation at least through 1957, and therefore the administration had to be concerned about integration at UT because it would affect their appropriations,” Dugger said.

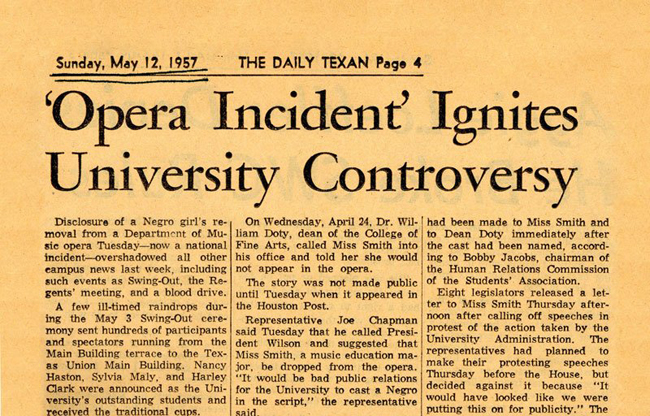

The Daily Texan supported the UT administration’s pandering to racist legislators in 1957 when Barbara Conrad Smith, who came to the University the previous fall as part of the first class of accepted African-American undergraduates, was forced to resign her part in an opera production after she won the lead role opposite a white male. State Rep. Joe Chapman insisted Smith, who had spent six months rehearsing for the opera, be removed.

The Texan criticized the selection committee that awarded Smith the part.

“Even if the girl chosen had the best voice, and we do not doubt that she did, it would have seemed only the better part of discretion and wisdom not to cast her in a romantic role opposite a white male lead,” the editorial board wrote.

Smith’s removal may have set minority students back, but change was on the horizon. In the 1960s UT saw an explosion of student activism, recalled alumna Alice Embree, who enrolled at the University in the fall of 1963 and took part in civil rights on campus.

The Texan didn’t delve into the problems driving the issues or produce much coverage of minority students’ struggles on campus, Embree said.

“The long term problem was that the Texan would ignore the problem until student activists made it an issue, and then they would cover what happened and begin to open up the dialogue,” Embree said.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s the population of minority students on campus grew, and the battle for ethnic studies centers and courses allowed the contentious issue of race in higher education to continue simmering on the pages of the Texan before reaching two major flashpoints in the 1990s.

In 1991, the Committee for Open Debate on the Holocaust submitted to The Daily Texan a full-page advertisement contending the historical accuracy of the Holocaust. A unique policy of Texas Student Publications, now called Texas Student Media, required the members of the Board of Trustees’s advertising committee to publicly debate and vote on contentious ads. Once the press got wind of the possibility of the ad running, a passionate debate erupted across the state.

“At one point we had hundreds of letters coming in from synagogues in Houston, telling us not to run the ad,” said Geoff Henley, editor of the Texan in 1992.

A version of the ad eventually ran without the editorial board’s support after advertising professor John Murphy, a member of the TSP board who still works at UT, convinced the other student members of the board that the value of free speech outweighed the potential racist tone of the advertisement.

Students distributed flyers on the West Mall labeling him a racist and a barrage of other personal and physical attacks. Murphy said these allegations were not true.

Marketing administration professor Eli Cox symbolically resigned from the TSP board after the vote to run the ad was made.

“I did not think any reputable professional newspaper would have printed that ad,” Cox said.

After receiving much criticism, Henley said controversy at the paper died down. The peace did not last.

Toni Nelson Herrera was an incoming history graduate student at UT in 1997 who arrived on campus shortly after the Hopwood v. Texas ruling of the previous year that struck down the UT law school’s affirmative action policy.

In an April 18, 1997 editorial in the Texan, current law professor Lino Graglia wrote: “The only reason we have racial preferences, of course, is the fact that blacks and Mexican-Americans are not academically competitive with whites and Asians. Racial preferences is simply an attempt to conceal or wish away this unwelcome fact … Racial preferences are the root cause of virtually all major problems on American campuses today.”

Herrera said she and other students of color decided to organize in response to professor Graglia’s comments. A rally of 5,000 people, including an appearance by Rev. Jesse Jackson, took place, Herrera said.

“I was targeted very specifically by The Daily Texan after I spoke up at the rally, saying something to the effect that I had low test scores,” Herrera said. “My SAT scores weren’t that great. Nevertheless I double majored and graduated from undergrad in three years. The point I was trying to make was that we should be looking at a whole range of factors to get into college.”

The Texan zeroed in on Herrera and fellow graduate student Oscar de la Torre, she said. Both student activists became the target of editorials, and de la Torre was depicted in a cartoon on horseback wearing a sombrero and carrying a rifle. After organizing demonstrations against the paper, Herrera said she and de la Torre took action against the newspaper’s racist actions.

“It was a formal complaint we filed with the newspaper,” Herrera said. “Unfortunately, not much came of it.”

Editor Colby Angus Black later received a 17-1 vote of no confidence from the staff of the Texan and was reprimanded by the Texas Student Publications board for allowing the cartoon to go to print and making personal attacks on students.

The outcome of the controversy wasn’t all bad however, Herrera said.

“The other side of it was that there was a section of students that worked for the newspaper who were more progressive and wanted to understand the movement and understand the struggles of students on campus so they could reflect that in their journalism,” Herrera said.

The Texan still faces criticism for its coverage and portrayal of race. In March 2012, the Texan once again published a racially-charged cartoon, this time labeling the death of Florida teenager Trayvon Martin as a “poor innocent colored boy.” The editorial board later apologized and decided it would not publish artist Stephanie Eisner’s cartoons for the rest of the semester.

Jensen said there are steps the Texan can take to improve coverage of minorities.

“To change, The Daily Texan will have to commit to the project of trying to transcend its racist past and the white supremacist culture,” Jensen said. “One thing that will have to happen is that the staff has to go through a brutal process of self-reflection,” Jensen said.

Since the cartoon’s publishing, The Daily Texan has taken steps to better address the needs and experiences of minority students on campus through its current and future coverage. A workshop with professors and local journalists, meetings with students from organizations that represent students of color and a series of stories spotlighting issues of race on campus, including this story, have been first steps.

“Hopefully, moving forward the Texan will have better coverage of the entire campus community and better representation of all of our students,” current Texan editor-in-chief Viviana Aldous said.