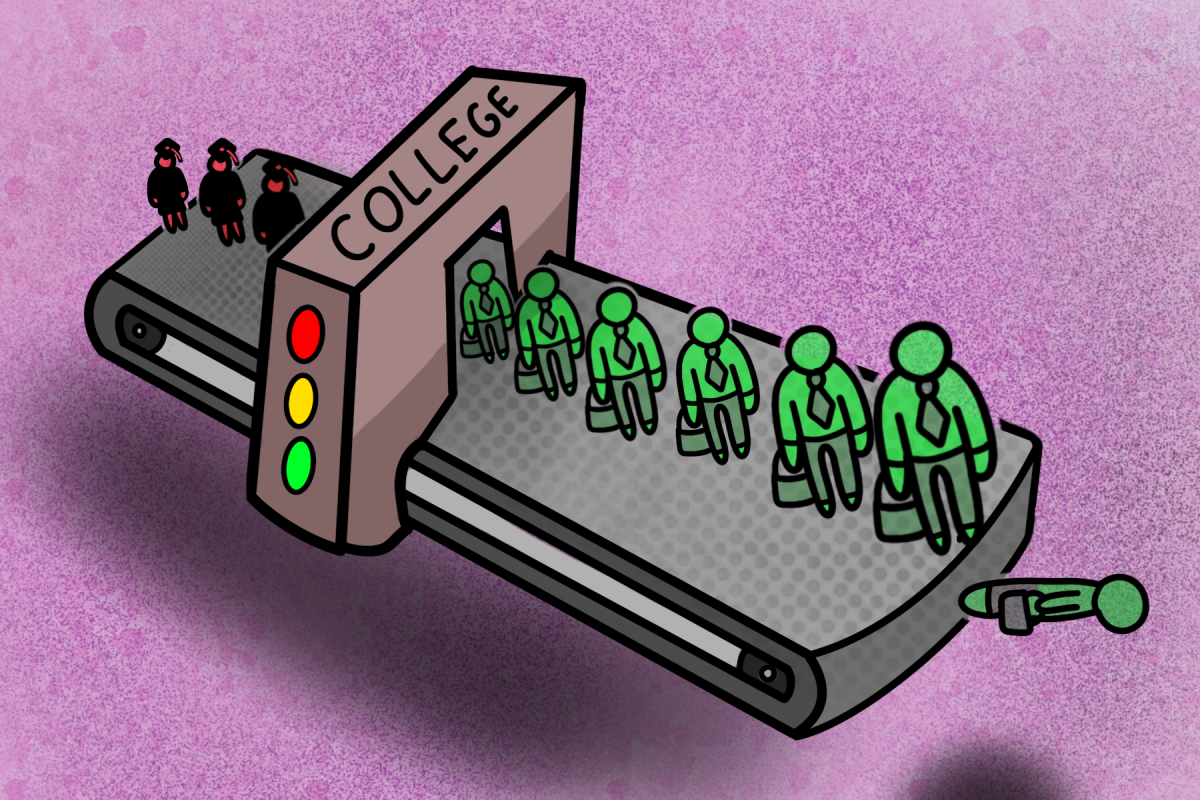

UT graduates 52 percent of its students within four years. That’s a terrible mark in comparison to those of other highly ranked public flagships, like the University of Virginia (86 percent, as of 2014) and UC Berkeley (72 percent, as of 2012).

The school’s administration has tried to raise that number in recent years, and it hopes that 70 percent of the class of 2017 will graduate on time. In pursuit of that goal, the provost’s office recently implemented an initiative designed to nudge rising fourth-year students into graduating by next May.

Promoting four-year graduation should benefit both students and the University. Those who graduate on time wind up spending less in tuition and, ideally, earning salaries earlier than those who don’t. From the school’s standpoint, a high rate of student turnover means more future donors and a boost in the irrationally important yearly college rankings.

But don’t expect the new policy to have much of an impact. By offering carrots to students who commit to graduate when they’re supposed to, the initiative carries the implication that UT’s lackluster four-year graduation rate is the consequence of an aimless student body.

That scenario rests on the implausible premise that a high proportion of belated graduates are simply choosing, for one reason or another, to accumulate several thousand dollars’ worth of extra debt and delay their entry into an increasingly competitive job market.

It’s more likely that delayed graduates get waylaid by coursework-related problems. Those could stem from a wide variety of factors, like excessive Q-dropping, rigorous dual-degree programs and a flawed registration system. The first two issues are difficult to address without promoting grade inflation or consolidating general education requirements across different colleges. But neither of those solutions would be easy to implement, and the former is ethically sketchy enough to risk endangering the University’s reputation.

Fixing registration, on the other hand, is a simple way to help push those in danger of graduating late back onto the four-year track.

Last year’s revamp reordered registration times based on a student’s degree completion percentage rather than their classification, helping seniors avoid the nightmare of getting closed out of a required course and having to put off graduation. But it created a lot of problems for underclassmen in the process.

Because their degree progress largely depends on the number of credits they earned as high schoolers, there’s a huge variation among registration times for first- and second-year students, and those at the back of the pack can find themselves locked out of important requirements and prerequisites.

Not only does that stall their progress toward graduating, it prevents them from getting earlier registration times in the future by curtailing their degree completion, driving them into an unavoidable doom loop of terrible course access.

The problem is even more severe for internal transfers, many of whom have accumulated an olympiad’s worth of hours in their previous majors without making any progress toward their new desired degree. Students who change their majors midstream already face an uphill battle toward graduating on time, and the new system does them no favors.

If the University wants to maximize its four-year graduation rate, it should structure the registration period such that the longest-tenured students (measured by the total number of enrolled semesters) get the first chance to design their schedules, regardless of the number of hours they’ve taken or how close they are to finishing their degree.

Students in the same prospective graduating class can be ranked by the number of hours they’ve taken so that those who have already completed their general education requirements don’t wind up stuck in redundant or unnecessary classes. That kind of system would send a lifeline to those currently left behind without hurting anyone on the cusp of graduating. Its biggest downside is that it could disadvantage anyone who plans on graduating early, a problem that could easily be allayed through the academic advising offices of individual departments.

There’s no reason for a student’s MyEdu dream schedule to go as soul-crushingly awry as a March Madness bracket or a New Year’s resolution. If the University plans on boosting its graduation rate through institutional support, it should focus its efforts on the AP-less freshmen and major-switchers who could otherwise wind up stranded at school for half a decade. Offering benefits to students who choose to graduate of their own accord does nothing to help those who the registration system has left without such a choice.

Shenhar is a Plan II, government and economics sophomore from Westport, Connecticut. He writes about campus and education issues. Follow Shenhar on Twitter @jshenhar.