Last week, President Gregory Fenves released the results of a study on the prevalence of sexual misconduct at the University. In this report, the administration reasserted its commitment to preventing sexual violence among students. However, the University’s response operates within an outdated framework for handling sexual violence and ignores several key factors contributing to its prevalence.

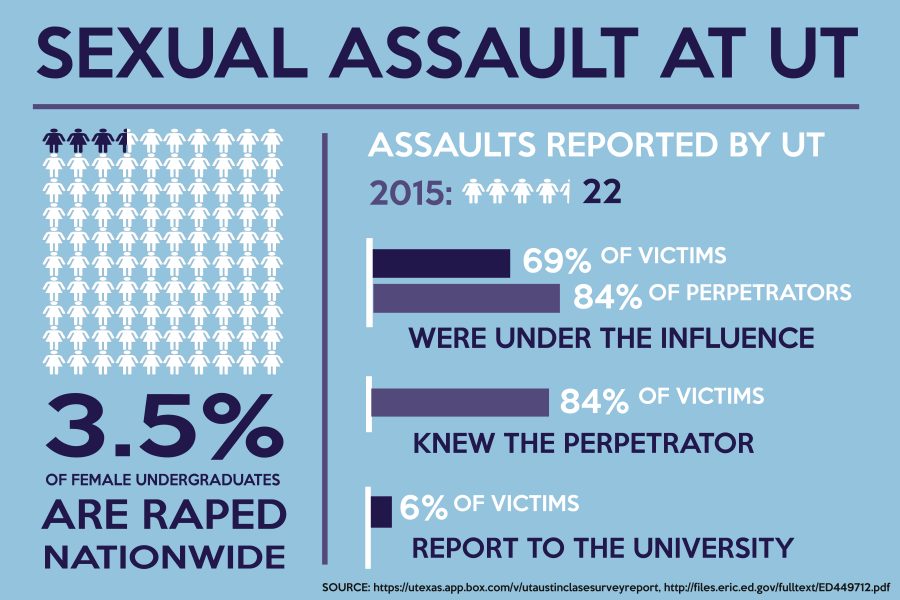

The survey alludes to a disturbing trend of underreporting sexual assault. According to a 2000 study, a conservative estimate says that on average, 2.8 percent of undergraduate women nationwide will be sexually assaulted within a given academic year. Assuming UT conforms to national standards, this means that 875 UT women are sexually assaulted annually. In fact, the survey reports that 15 percent of undergraduate UT women have been raped — approximately 3,750 students. In UT’s most recent report of crime on campus showing data for 2015, the University disclosed a total of 22 reported sexual assaults, hardly 1 percent of the female student body.

Justifications for this inequity begin with the difficulties of reporting rape. Victims of sexual assault often fear the social consequences of coming forward and keep quiet to avoid further trauma. The report indicates that 68 percent of victims at UT said nothing of the assault to anyone, and only 6 percent reported the assault to the University in some way. This data suggests that an overwhelming amount of UT students do not know how or do not feel comfortable reporting an assault to the University.

Problems in underreporting can also be tied to cultural misconceptions about sexual assault. The most common rape myth is that of the “stranger rapist.” While some sexual assaults are perpetrated by strangers, they are in the minority. The UT study found that 84 percent of rapes were committed by an acquaintance or friend. Despite this, the study continued to use wording that perpetuates the myth. By asking to students about their level of comfort “walking across parking lots” or “walking across campus at night,” the study ignores the fact that its own data underwrites the legitimacy of this mindset. It asked no questions focused on students’ perceived safety while hanging out at a friend’s apartment or attending a fraternity party — where they are objectively in more danger.

This outdated way of looking at the problem of rape is mirrored in many of the school’s response initiatives. Campaigns like Be Safe and SURE Walk overwhelmingly focus on safety when walking alone, where only a small minority of assaults actually occur. This misplaced focus pulls attention from situations that are more likely to pose actual harm but seem innocuous because students have been trained to fear the unlikely stranger in the shadows.

Further complications arise from misunderstandings of consent and sexual assault when alcohol is involved. Studies have found that as many as half of women who meet the legal criteria for having been sexually assaulted do not consider their experiences rape. The definition of sexual assault often appears hazy, especially with the prevalence of alcohol in questions of consent. However, government sophomore Austin Smith, resident advisor and Voices Against Violence member, credits campaigns advertising consent with increasing bystander intervention. Such campaigns “show survivors that students on campus don’t tolerate assault,” Smith said. Despite notable successes, questions of consent remain difficult to answer when both parties are intoxicated, and the University has yet to express a strong stance that students can use to guide their behavior in questions of alcohol and consent.

In order to develop an effective means of addressing sexual violence on campus, the University needs to update its worldview. The administration needs to acknowledge that the overwhelming majority of rapes occur off-campus, under the influence of alcohol and at the hands of friends. The myth of the stranger rapist is significantly easier to handle, but the real problem of rape at UT cannot be solved by telling students to use the buddy system when they walk home at night. This approach ignores the reality of the situation and allows difficult questions about university culture to remain unresolved.

Anderson is a Plan II and history freshman from Houston. She is a columnist. Follow her on Twitter @lizabeen.