When the University released the results of a campus-wide study on sexual assault last month, they were accompanied by a myriad of promises to recommit to eliminating sexual violence. One arena in which the University has remained silent, however, is the association between Greek life and rape. The administration’s unwillingness to recognize fraternities as a hotbed of sexual assault reflects a troublesome dereliction of the duty it owes its students.

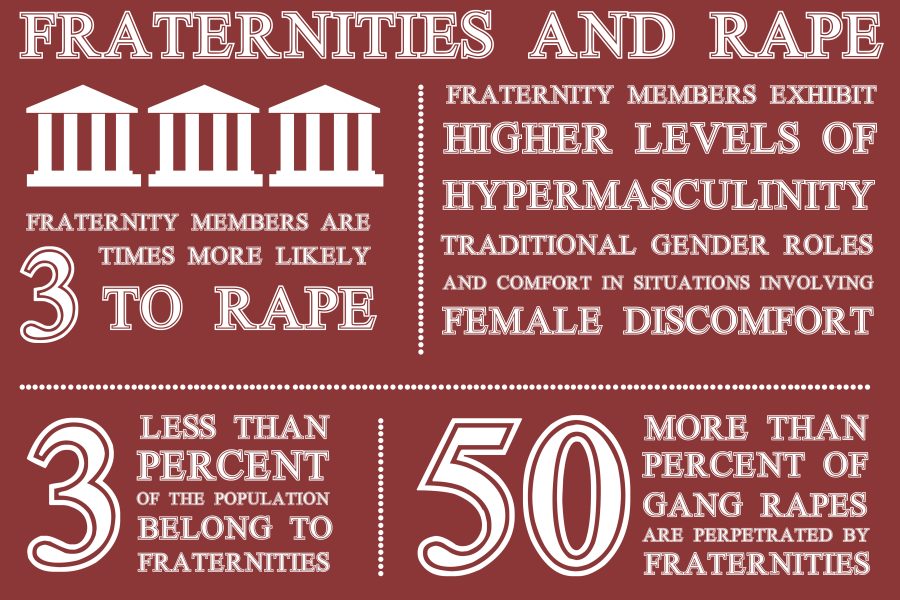

Studies have linked fraternities to rape for decades. Belonging to a fraternity is a “significant predictor” for sexual aggression; nationwide, fraternity brothers are three times more like to rape than their peers. Fraternity men commit more than half of all gang rapes.

Whoever has the alcohol has the power, and at fraternity parties, the boys have the alcohol. Sororities are not allowed to distribute alcohol, so they are forced to party in the territory of fraternities – where the boys control the alcohol, the environment and ultimately the girls themselves.

Nationally, as many as 75 percent of sexual assailants are under the influence of alcohol. At UT, it’s 84 percent. The near-ubiquitousness of alcohol at fraternity parties combines with a male-dominated sphere and the expectation of casual sex to create volatile situations. Add in some alarming perception differences demonstrated by fraternity men and rape becomes — according to one University of Georgia sociologist — a “virtual inevitability.”

Fraternity boys exhibit higher levels of hypermasculinity, more traditional attitudes toward gender roles, and — most disturbingly — higher levels of comfort when confronted with female pain. All of these are strong predictors of sexual violence.

Hypermasculinity, expectations for casual sex, and alcohol consumption are integral to the culture of fraternities and intimately linked with sexual violence. Rape culture is in many ways indistinguishable from fraternity culture.

No data is available on the link between Greek life and sexual assault at UT; the University’s sexual assault survey makes no mention of fraternities. All of my assertions about fraternities and rape on this campus are claims based on national averages because the University, by failing to address and fully research the problem, has given me no other choice but to guess.

A representative from the Office of the Dean of Students acknowledged that “there is a history (in the fraternity community)” of sexual violence and noted that they have specific policies geared toward addressing it. However, she was unable to cite these policies and neglected to follow up with me regarding specifics. When I reached out about what could distinguish fraternities at UT from these national trends, the Texas Interfraternity Council president did not respond to a request for comment.

Colleges and universities across the country — many of them public schools — have taken steps in recent years to eliminate fraternities or to place restrictions on their alcohol consumption. The Justice Department has put pressure on universities to address rape in fraternities and off-campus Greek life, but many schools — including UT — are hesitant.

The University has the authority to limit sexual violence in fraternities. As registered student organizations, fraternities are subject to specific and expansive privileges, all of which could be revoked simply by the Dean of Students deciding that a “preponderance of the evidence” suggests a link between a certain organization and a violation of the student handbook. And yet, nothing of this sort has happened at UT.

It is within the University’s reach to sizably reduce rape at UT, and yet no steps have been taken to highlight the community perpetrating a disproportionate number of assaults. No research has investigated the prevalence of this issue at UT. There is an irrefutable link between fraternities and rape, and by ignoring it, the University prioritizes the enjoyment of some students over the health and safety of others.

Fraternities, as we know them, shouldn’t exist. They’re an outdated relic of an antiquated system based on strict hierarchies and institutionalized gender violence. But as long as they do, the University must pay specific attention to their behavior.

Fraternities are a powerful social class on campus. And as long as more prospective students are attracted by UT’s Greek life than are scared away by the fact that 15 percent of UT women are raped, this problem is unlikely to go away. As long as the University continues to ignore this correlation, it puts the well-being of its students at risk. As long as the question of rape culture within fraternities goes unresolved, the administration must recognize that when UT President Gregory Fenves tells us that “one sexual assault is too many,” we know he’s lying.

Anderson is a Plan II and history freshman from Houston. Follow her on Twitter @lizabeen.