It’s flu season, that time of year where everyone in your exam room seems to be sniffling or coughing. And while the University Health Services do the best they can in working to prevent the spread of flu, there is another way they can indirectly combat the spread of the flu and other diseases.

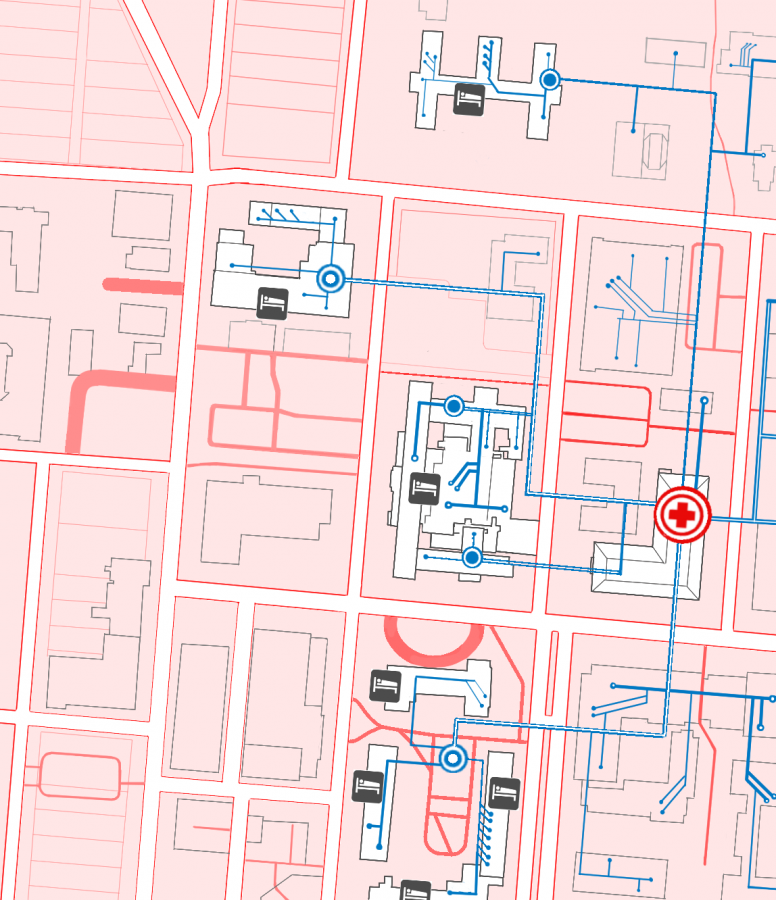

Currently, for patients who feel ill and schedule an appointment, UHS does not inquire where they live. However, this information, coupled with the patient's diagnosis, can prove valuable when released to the public raising caution to prevent the disease from spreading..

In 2013, an outbreak of bacterial meningitis across Princeton University afflicted nine students. The one student who died was visiting Princeton from Drexel University and had come in contact with students who had likely been carriers. Even after the remaining students had recovered, some reported persistent neurological conditions as a result of the meningitis. This situation shows the need for a rapid dispersion of epidemiological data on college campuses.

Meningitis is classified as a “reportable disease” and must be reported to the Center for Disease Control by the health care provider. While the reporting process may not take longer than a day or two, the rapid progression of certain disease vectors makes two days too long. And even then, it may be another day before the university is able to release a generalized report of the outbreak. In the case of the Drexel student, a more rapid response to the presence of the meningitis might have persuaded them to avoid Princeton altogether.

Less serious diseases such as influenza, stomach flu, or the common cold are almost never reported to the CDC. However, within the microscale of a college campus, reporting where such diseases originate could help raise awareness and prevent the spread of these diseases across a population.

Any student who spent time living in one of the dormitories, especially Jester Residence Halls, has likely heard of a “new bug going around” at some point. While such illnesses are often not serious, they spread quickly in the petri-dishes that are college dormitories, no doubt accelerated by students’ ignorance to the presence of the disease.

Information regarding the origin and number of cases of such diseases could benefit the campus as a whole. Individuals could take more care with nutrition, hygiene and upkeep of vaccinations and potentially avoid the area in question. These practices would indirectly raise the herd immunity, or the immunity of the population as a whole, and reduce the persistence of diseases.

Patient privacy comes to mind as the biggest roadblock of the dissemination of this type of information. Privacy is closely guarded and regulated by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. However, as the patient could not be identified based on location and disease type, such information release does not appear to breach HIPAA privacy rules. To further anonymize this information, this could be provided as an opt-in service and incentivized by UHS.

Hopefully, the merit of making this information available is understood. As flu season is right around the corner, this a small but significant way that UHS can indirectly bolster students’ fitness and performance.

Batlanki is a Neuroscience sophomore from Flower Mound. He is a columnist. Follow him on Twitter @RohanBatlanki