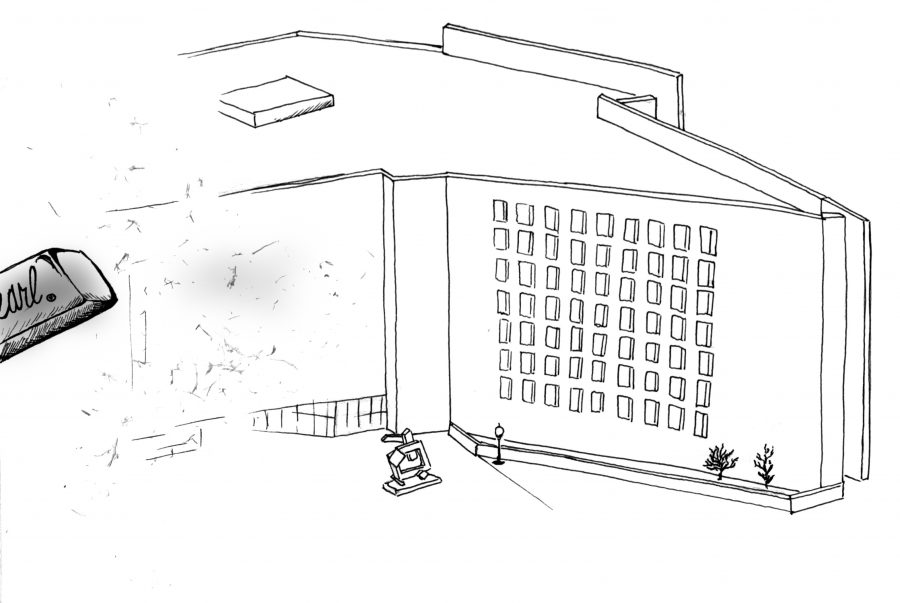

There are many beautiful, old buildings on the UT campus whose utility belies their age. Light filtering through the long windows onto the worn tables in the architecture library makes studying pleasant. The Perry–Castaneda Library isn’t like that at all. The building’s age is most evident in what it doesn’t bring in: light. In true brutalist fashion, the building transforms studying from a chore into agony.

Slabs of Indiana limestone, interspersed with blocks that seem large from the outside but rarely let light reach the vast interior of the library, command the exterior of the PCL. Many places where students study, such as in group study rooms or the Scholars Commons, instead rely on fluorescent or LED bulbs, which can trigger headaches.

The lighting is only a larger symptom of the PCL’s problems: The building is too old and not built for the hordes of students who visit the library, week by week. UT can do better, either through extensive renovations to bring in more light, or if that isn’t enough, a new building. This isn’t just a matter of appearance. Research links higher quality of life and physical activity with working in natural light zones.

Travis Willmann, communications officer for the UT Libraries, said the library wasn’t designed for the demands of today. “The

university has grown. The city has grown. The need for facilities has grown. The student population has outgrown the building,” he said. “The building was designed in 1977 for the population that existed in 1977.”

The UT administration is aware of the PCL’s aging structure so they decided to tinker around the edges. Willmann said that maintenance workers are slowly retrofitting the fluorescent lights with LED bulbs, which are friendlier to the eyes. In recent years, they have developed the “Learning Commons,” which includes the University Writing Center, new common study spaces and more. The new spaces ensure that we keep up with the digital age, but they don’t let more light into the building, which is the central problem. When studying in the PCL, one still hears the buzz of artificial fluorescent lights from the ceiling in an unnaturally bright building. The new computers are nice, and the LED lights might be a little easier on the eyes. But natural lighting, unlike technology, can’t be bought — it can only be brought in.

Willmann said maintenance workers are replacing the harsh fluorescent lights with softer LED lights, but the University needs to think bigger. UT’s 2013 campus master plan includes plans to revitalize old buildings on campus like the “Six Pack” and scientific laboratories, but there are no plans, Willman said, to let more light into the PCL. With the budget cuts from the Legislature and the pressure to improve student financial aid, many other priorities compete with the completion of a new library.

But if UT-Austin managed to construct a beautiful $310 million engineering building with both private and state funds, a new library should be a priority, even if a full fundraising effort can’t be made for a couple of years.

The new Austin Central Library offers a luminous contrast to UT’s academic dungeon. Light washes over 80 percent of the interior of the building. Wooden pathways connect common areas, group rooms, library stacks, and quiet study spaces. An outdoor roof garden on top of the building offers stunning views of Austin and a restorative place to study or simply hang out. As economics and government sophomore Jay Do said when visiting the Central Library for the first time, “It’s a lot more modern, open and airy. It’s a lot more relaxing.”

If only we could say the same thing about studying at the PCL.

Wong is a plan II and government senior from McKinney.